Sunday Drives

Archive of a bi-weekly newspaper column on vernacular architecture, written for the Lawrence, MA Eagle-Tribune, from 1988-1999. In 1994, the column received a Massachusetts Historic Preservation Award.

Each "Sunday Drives" column was limited to 250 words, so when writing them I focused on explaining a few interesting elements from each building, instead of telling its complete history.

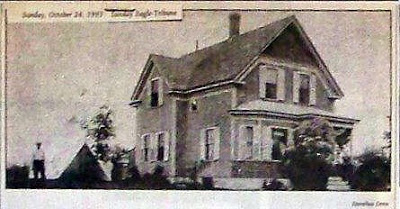

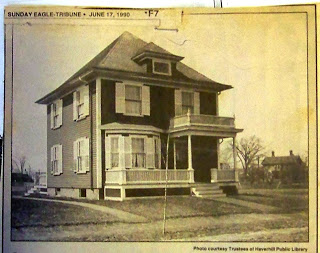

#121 - 10 Maplewood Ave., Methuen (10/24/97?)

This style is well adapted to those narrow city lots

Some house layouts have names. "Ranch" brings to mind a one story house with a front door on one side of the living room. "Colonial" suggests a two story house with a centered front door which opens into a hall with a room to the left and another to the right.

This particular house was built in about 1902, the first house on Maplewood Avenue. Charles Wilkerson, the man standing in the yard, was the owner, and his family still lives here today. If you drive up the street, you will see several other houses built soon after this one, in the same pattern, the one across the street being the closest copy. Although this house is now covered with vinyl siding, on the house across the street the dentils still run up the eaves and across the gable, a Colonial Revival detail that manages to look charmingly Victorian as it outlines the side, front and bay window of the house.

The owners have the 1902 contract for the house, a standard 12 page form with spaces filled in by the builder, Richardson Brothers. They add a note that the house is one foot larger in all directions than the plan specified. That's why this house looks ample and broad, not quite as up and down and snug as its mate across the street.

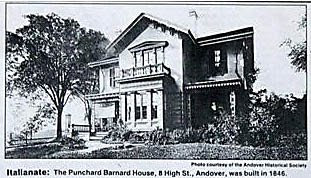

note: I was asked to write this column as a birthday present for the first owner's grand-daughter. I was happy to comply. It was fun to give her a surprise when she opened the newspaper that Sunday morning.

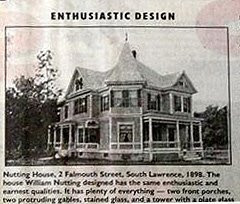

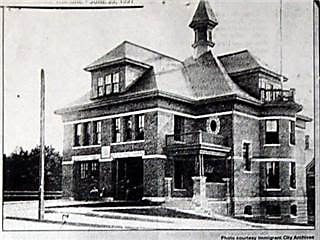

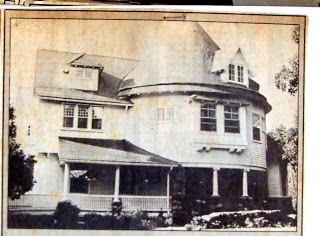

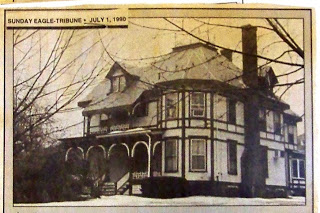

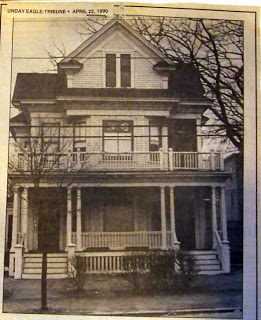

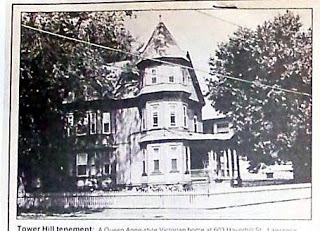

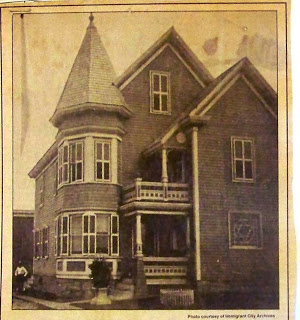

#120 - Nutting House, 2 Falmouth St., Lawrence, 1898 (10/93)

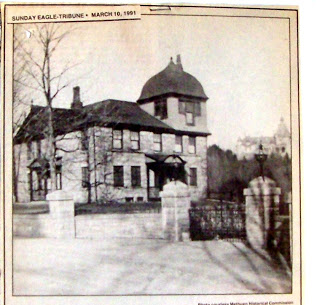

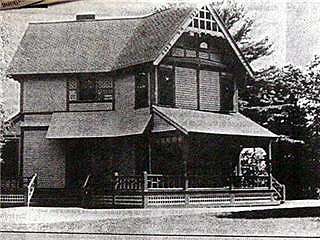

Nutting House is fanciful Victorian; original photo courtesy of Immigrant City Archives

William P. Nutting, a carpenter, built this house in 1898 as his home and office. He used this photograph to advertise his business in the 1899 Lawrence Street Directory. His ad states that repairs will be “Neatly Done and Promptly Attended To,” and that estimates will be “Cheerfully Given.” The house, which he designed, has those same enthusiastic and earnest qualities. It has plenty of everything – two front porches, two protruding gables, stained glass, and a tower with a plate glass window facing the corner, which looks down on the intersection of Exeter, South Union and Winthrop streets, eager to see and be seen. Although the design leans toward the new style, Colonial Revival, with its symmetrically placed windows and gables, it is still fanciful Victorian – the windows are symmetrical around the tower with its curving roof and finial, not balanced on either side of the front door in colonial fashion. The frieze and corner boards are colonial, but all the wall surfaces are outlined, and those below the windows are finished with flat siding instead of clapboard. Also, the enthusiasm for surface decorations and mouldings on mouldings – so common in the Victorian years – are still present.

William Nutting’s name first appears in the Lawrence Street Directories in 1895, as a boarder at 74 Bailey Street, and by the 1898 edition, he has moved to this address. But by 1904, he is listed as a foreman for Pike and Sons, Contractors, and lives in Methuen. Then he disappears from the directories. Note the fields and woods behind the house in the photograph. Today the land is a parking lot and the Monomac Mills complex.

(I think you can see the house in its current setting if you rotate through the 'street view' at this google maps page - ed)

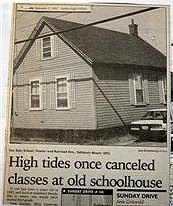

#118 - Sea Side School, Fowler and Railroad Ave, Salisbury Beach, c1893 (09/09/93)

High tides once canceled classes at old schoolhouse

If you had been 6 years old in 1893, and lived at Salisbury Beach, this is where you would have started first grade. Your teacher, Miss Gertrude Richards – who earned $4 a day, plus board – would have been waiting for you and the other first-, second- and third-graders when you arrived for your first day. This is a very small school building. There is no space here for the standard two front doors, one on the left for boys, one on the right for girls, or even a cloak room. There is only the classroom. But its builder, William Charles Pike, did not skimp on style. He bound the eaves by a crown moulding, and returned them neatly to a wide frieze board at the top of the clapboards. Today, 100 years later, the original siding and mouldings are still there. Notice how the school sits well above the ground, above most flood water. Even so, the records show that when the tide was especially high, school would be canceled.

The trolley along the beach ran down Railroad Avenue to the mouth of the Merrimack River at Black Rocks. A second line ran into Salisbury itself. In 1917, the Sea Side school was closed and the children rode the trolley to school in town instead. (Any idea why the school closed? Too much high tide, or too many students? And when the trolley line went in? Are the two at all connected? - ed) Today, the school looks much like the summer cottages which surround it. Its roof line, its plaque and its extra yard – probably the children’s playground – remind us of its origins.

(I've spent a lot of time looking for more info on the trolley that used to run here, but only came up with a few brief passages from books scanned by the GDP. These include page 88 of Whittier-land: A Handbook of North Essex, written by Samuel Thomas Pickard and published in 1907, and page 130 of By Trolley Through Eastern New England, written by Robert H. Derrah, and published in 1904. - ed)

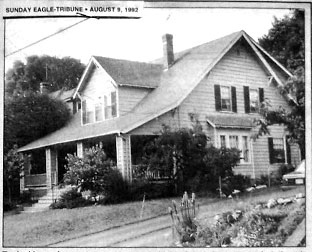

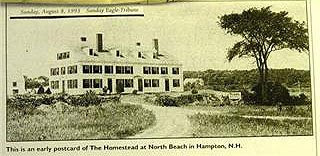

#116 - The Homestead at North Beach, Hampton, NH, c1830 (08/08/93)

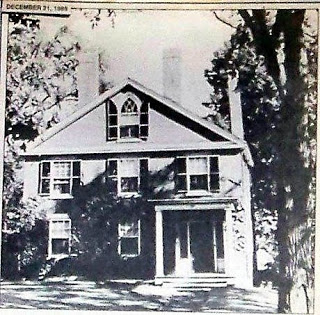

200 years at the beach: House has gone with the flow

This postcard of The Homestead on Hampton’s North Beach seems easy to decipher – a Greek Revival farm house built around 1830, its gable detailed as a pediment, facing the sun and High Street. Its barns to the left, it seems to be a farm that became an inn, as the beach became a tourist destination. Then I talked to the current owners, who are only the fifth family to own the house, and read Joseph Dow’s 1892 book, History of Hampton. They told me that the house was built by John Elkins on the knoll called Nut Island, just off North Beach, around 1800. Moses Leavitt bought it in 1802, just before the birth of the fifth of his twelve children.

The 1806 map of Hampton notes M. Leavitt’s tavern at the edge of the beach, so this house has in fact been a hotel for almost 200 years. That surprised me. I expected farms and fishing shacks at the beach in the early 1800s, but why a hotel? Who stayed here? The answer is that fishermen and fishmongers from Vermont came in the winter, and bought frozen fish to sell back in Vermont and Canada. While they were there, the barn housed their wagons and horses. Leavitt’s tavern had a summer trade as well – houses at the beach are listed as taking summer boarders as early as 1826. Dow’s History calls the Homestead ‘famous’ and notes that it is currently (in 1892) being run by Leavitt’s grandson, Jacob.

Over the years the house has grown from its original one story size. The corner pilasters, the square moldings at the windows and doors, and the tall stately chimneys probably all date from an expansion in the 1830s. Today, the house has balconies all around, and is called The Windjammer. The stone outcropping seen to the left in the postcard is now the edge of the town parking lot.

(aerial photo taken in 1929, and is from the Lane Memorial Library's excellent online archives -ed)

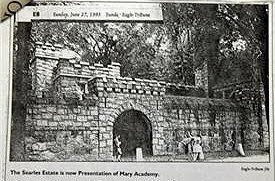

#115 - Searles Estate / Presentation of Mary Academy, c1891 (07/27/93)

Stone Cottage beats sun, sand near the seashore; postcard courtesy of Hampton Historical Society

magine a knight standing under that stone arch, before an oaken door. Looking out, he would control the space, easily barring the curious visitor. Overhead are slits for the arrows of bowmen, and above that the parapet extends out, giving the defender, protected by battlements, a good view of any intruders. The walls are well built – rubble, then cut stone topped by solid caps to keep the water out. If the first wall is breached, two more protect the king within. So what is this incredible structure doing in Methuen? Edward F Searles, who built this wall, liked castles - he built two, this one in Methuen, and another in Windham, NH. And, he had a good reason for his walls. Mr. Searles was an interior decorator, traveling across the United States and around the world for interior and furniture designers, the Herter Brothers, when he met a widow, Mrs. Mark Hopkins of San Francisco, and married her. She was 22 years older than he, and when she died – leaving her estate to him – the will was contested. The case, tried in Salem in 1891, was covered daily by the national press. So, like modern day celebrities, Mr. Searles wanted his castle walls for privacy.

Stephen Barbin of Methuen, Mr. Searles’ biographer, adds another reason for the walls – Edward Searles’ association with The City Mission (a Catholic charitable society) in Lawrence, on Jackson Street. He knew that many of the Italians who had recently come to Lawrence could not find work. So while Mr. Searles and his architect, Henry Vaughn, designed the walls, and the master stone masons, Billy May and Alex Stone, built them, Mr. Searles hired the unemployed Italian immigrants to gather the stone (from where? - ed), enough for six miles of walls.

After Searles' death in 1920, some of the buildings became Presentation of Mary Academy, a Catholic girls' school. When I wrote this column, the school was still on site and Searles' house was occasionally open to the public

(color photo is from the Castles of the United States website. -ed)

#114 - The Stone Cottage, Hampton Beach, 1894 (07/18/93)

Stone Cottage beats sun, sand near the seashore; postcard courtesy of Hampton Historical Society

Sun, sand and sea! The perfect summer combination, the reason for a house at the beach! Unfortunately, they are also the reason why beach houses look weather beaten. The salt air, the beating sun, and the blown sand are not easy on wood construction, to say nothing of the destructive power of blizzards and hurricanes. But look here, a stone bungalow, impervious to wind and sun, with a low roof and wide porch protecting the inhabitants within, as well as inviting the summer guests to relax and enjoy the weather and view. The stone columns at the porch are solid, their cornerstones and those of the chimneys neatly placed. The arches below are carefully laid up. These stones will only… ( missing text)…house will still be standing. (Missing text)…be etched a little smoother, articulated a little more finely by blown sand and salt water. In a storm the ocean will wash over and past the house, into the marsh behind.

The Stone Cottage, as this bungalow is referred to, was built by Mrs. Mary Aiken in 1894, as her summer house. She lived in Franklin, NH, but had grown up locally – the mill stones above the second floor windows came from her family home in Hampton Falls. The bungalow style focused on natural materials . Stone piers were common, with deep mortar joints that emphasized and articulated each stone’s shape and size. Here you can see that each stone was placed so it could be noticed and appreciated by the idle lounger on the veranda.

This photo came from the postcard collection of the Hampton Historical Society, which has an excellent collection of maps and object dating back to the 1600s, and postcards from the late 1800s and early 1900s, including relics from the trolley line that ran in front of the Stone Cottage from 1897 to 1926.

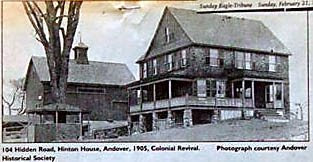

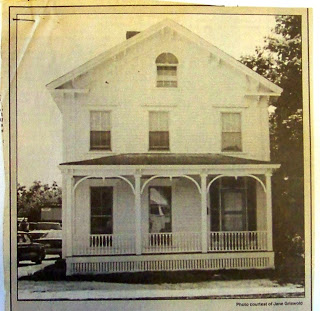

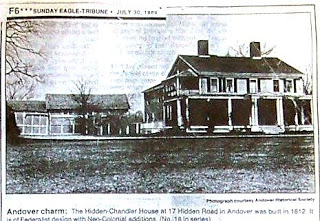

#106 - Hinton House, 104 Hidden Rd. Andover, 1905 (2/21/93)

House that ice cream built owned by former slave

I passed this house and barn many times, catching a view of it behind trees and shrubs, before I connected it to this photograph. Today the barn is painted red, the house is white. It sparkles. The house and barn in the photograph have earth- toned dark walls and roof, stone columns. These natural colors are what the architect, Perley Gilbert, intended when the house was built in 1905. Built in the latest fashion, it was a symbol of the success of Allen and Mary Hinton, who ran the Hinton Ice Cream Co., in Andover from 1877 to 1922.

Allen Hinton was born a slave in North Carolina. In 1864, he moved to Andover and began selling snacks from a wagon to Phillips and Abbot Academy students. Then someone suggested ice cream might sell well. So Mary, his wife, made the first 2 gallons, and by the early 1900's they were selling hundreds of gallons a week from their wagon and at the South Main Street store. The pavillion around the tree in the photograph served the customers before the store was built.

In 1901, Mr. Hinton was able to buy the farm where he had been a tenant at auction for $525. He immediately built a new barn - the one in the photograph - and an ice house. He hired Perley Gilbert, whom he had known at Phillips, to design the house. It is a restrained design - spacious, with large windows, including a broad bay, a gracious porch with elegant detailing in the roof and railings. It uses the vocabulary of the Colonial Revival style, but mainly this is a comfortable house for a successful framer and businessman.

A lot more about the Hintons and their ice cream company can be read in the files of the Andover Historical Society.

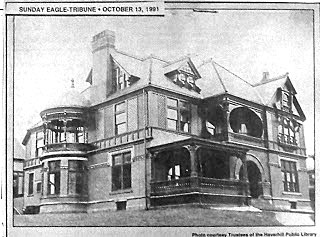

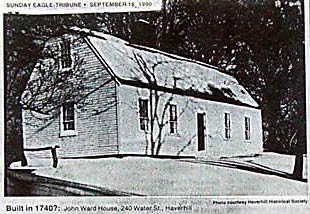

# 101 GFS Webster House, 1151 Broadway, Haverhill

Farmhouse moved but remained the same

In 1905, George Franklin Sargent Webster - at the plow in the photograph - and his wife - on the far right - posed on their lawn for this photograph which was made into a postcard.

The house behind them had been built 2 years earlier in honor of their marriage. The original farm house, a cape, was moved up the street to 1121 Broadway. The style of the house, Colonial Revival, contrasts with the barn, built about 1800. Both use the same boxy forms but put them together in very different ways. The facade of the barn is a flat surface with windows and doors placed in patterns determined by use and proportion - the door is square, large enough for loaded wagons, while the windows are centered on their spaces. The only hint of style is in the roof overhang and the return of the eaves.

The end wall of the new house repeats the lines of the barn. But the front of the house exuberantly breaks the flat plane with bay windows and columns. The roof is broken by the front facing gable whose steep overhang returns at the eaves to become the cornice for pilasters with elaborate capitals. Compare that to the barn's simple eaves and corner boards.

At the front door the flat pilasters become the background for round columns and their architrave - the band with its cornice above the front door. Again the flat two dimensional wall is pulled into three dimensions.

The house was originally yellow with white trim. Today it is dark brown. and those bits of trees in the photograph have grown to tower over the house.

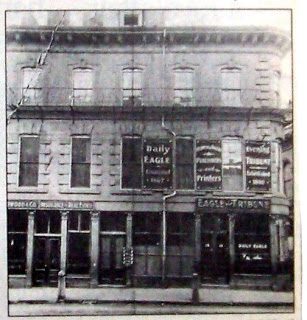

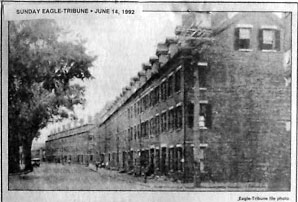

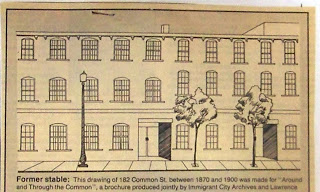

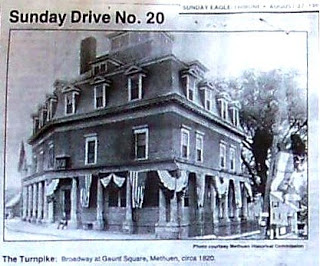

#100 305 Essex Street, Lawrence

Old Eagle-Tribune office was built in Italianate Style

Four years ago the people at the Eagle-Tribune gave me a chance to write about architecture in the Merrimack Valley. They didn't know if there would be an audience, or if I could meet deadlines. Nevertheless, they let me try. This column, the 100th, is to thank them for their support and encouragement.

305 Essex Street, at the corner of Lawrence Street, was the offices of the newspapers The Daily Eagle, The Evening Tribune, and the weekly Essex Eagle in 1890. Today the building's brick is exposed, but originally, as seen in the photograph, the brick was stuccoed to resemble cut stone, like buildings you would see in Florence or Rome - in other words, Italianate.

This building was designed to be seen from the street. The cast iron columns on the first floor allow large glass windows so merchants might display their goods to passing shoppers. Those columns, which could be as plain as the concrete filled steel columns in many basements, have bases, edges and flowering capitals, a treat for the pedestrian.

The fire escape becomes part of the ornamentation with its crossed railings. The eaves, embellished with brackets and mouldings signal the top of the office block. There is a 4th floor, but it is invisible to the pedestrian. As can be seen in the photograph, its dormers are simple, without the variety of pattern seen in the walls of the lower three floors. So the massive eave line becomes the top edge of the building.

#99 55 East Haverhill St., Lawrence

A city house good enough for a fairy tale

Look at all that Victorian gingerbread! all that fretwork in the gables labels the house as Stick Style.

The name comes from the pieces - sticks of wood - used to decorate the house. The horizontal banding below the windows and the same detail used to create the frieze band at the eaves are typical details of the Stick Style, as is the cross bracing under the windows. The house is built from 'sticks' - wooden studs set side by side and braced. The trim is seen as an outward show of that framing pattern.

This doesn't look like classic Greek or Roman architecture. The arches on the porch and the frieze band are the only pieces borrowed directly from that vocabulary. However, the house maintains the classic order of base (bottom), middle and top. The frieze, the banding, and the porch are also all so defined.

This house was built about 1875 by W.H.P. Wright, a counselor ( at law? city?) with offices on Essex St. Later the Church of St. Laurence O'Toole, which was on the corner of East Haverhill St. used the house first as a rectory and then as a novitiate. In 1987, Merrimack College opened its Urban Institute here. The house is now a center for seminars, classes,, and a home for student interns in urban studies. It is the focus of the college's programs for Lawrence High School students and its collaboration with the Frost Elementary School.

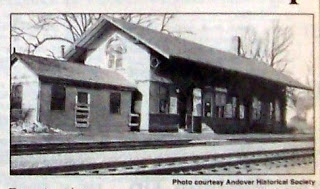

#98 174-6 Andover Street, Ballardvale, Andover

This home was once half of the depot for Ballardvale train stop

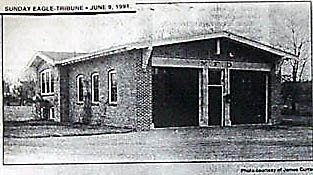

At 174-6 Andover St., Ballardvale, is a two story house with fancy double Italianate windows facing the street. The hood over the windows on the first floor is flat with brackets on each side. The second floor windows are arched within an elaborate arch with springing blocks at its beginning and a key stone at its top.The roof overhang extends so far to the sides and front that it needs brackets for support.

Why was this house built here amidst mill housing?

It wasn't. This house was once half of the depot for the Ballardvale stop on the Boston and Maine Railroad.

The photograph shows the station as it sat on the west side of the tracks. This end, probably the right end, was moved to Andover Street in the 1870's. The remaining half served as the depot until the 1950's when it was torn down.

The first railroad line through Andover was built in 1836 to the east of Ballardvale. Its railroad bed is still visible running through Rec Park and Spring Grove Cemetery on Abbot Street.

When the Shawsheen River was dammed at Ballardvale for water power, and the mills built, the tracks were relocated to their present location to the west of the river.

The station was built in 1848 in the style of the day, Italianate. The shape and details of provincial farm houses built of stone were adapted for an American railroad station built of wood.

The elaborate windows announce that this is an important building. The overhang originally meant to protect farmers and crops, here is extended so that it shelters passengers and baggage.

#97 1088 West Lowell St., Haverhill

A friend, describing the way houses changed from colonial days to the Victorian era, explained that they grew higher and higher, in feeling as well as reality. Drive up West Lowell Street in Haverhill to Scotland Hill and see.

This Italianate farm house sits on a knoll looking down the road. We, passing by, look up at it. Then its detailing makes it feel even higher. A curve at the top of the gable window, draws the eye up to the peak of the roof. Or see how the slender shape of the bay window, made by its four narrow windows is continued in the two long double windows just above it. From there one's eye goes to the skinny paired brackets and dentils in the eaves, and again to the roof.

Note how the brackets are bunched at the eaves' returns to act as mock Corinthian capitals to the slender pilasters on the corners of the house - a wonderful detail that reinforces the height of the house.

To the north, across W. Lowell Street, is a Georgian brick-end farm house probably built about 1800. Although it too is at the top of Scotland Hill, it sits solidly surrounded by its fields, a nice contrast to this house, built about 50 years later, so decidedly sited above its land.

Not much is recorded about this house. A local historian told me of the Polish and Armenian families who farmed here at the turn of the century. The 1851 Haverhill map lists "Dr. Merrill" next to the dot marking this house. Other houses on W. Lowell Street are associated with Ayre's Village, so perhaps this house is too.

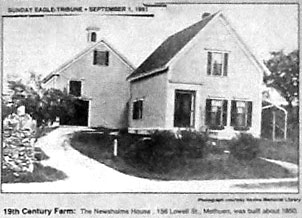

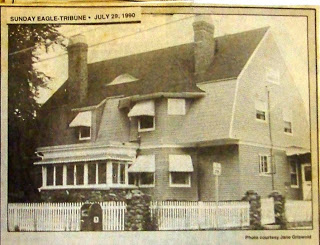

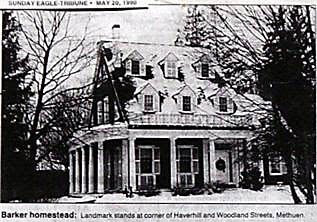

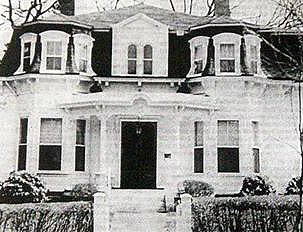

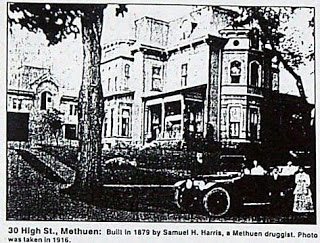

#96 Newsholme House 156 Lowell St., Methuen

Haverhill's 1890 Gale House typifies High Victorian style

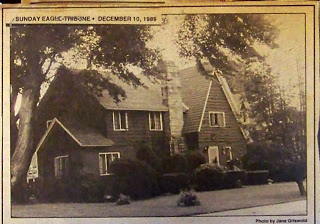

Newsholme house showed off the suburban side of Methuen

In 1903, Methuen printed a 'Pictorial Bulletin' for its Old Home Week Celebration. Its purpose was "To show something of Methuen, one of the Most Attractive Suburban Towns". Included in it was this picture of the residence of Alfred Newsholme.

Most of the turn-of-the-century homes shown in the booklet are stylish late Victorians. Compared to them, this house is plain indeed, hardly changed since its construction in the 1850's. A story and a half farm house, it has very simple mouldings. In the photograph, the curve of the frieze board at the eaves and the hoods over the windows and doors seem tentative. But seen on site, the details add up to an effective, graceful facade, fitting for the straight forward shape and relationship of the house, ell, and barn.

In mid-19th century fashion, the house faces the street. But note that the north wall - the left side on the photo - has only one window, protecting the house from the cold winds from the north. The lattice work to the right probably carried an awning for protection from the summer sun. This was a working farm, a barn with a hatch for hay over the door, and a lower level for implements and perhaps cows. It was possibly a truck farm, providing vegetables to growing Methuen and Lawrence.

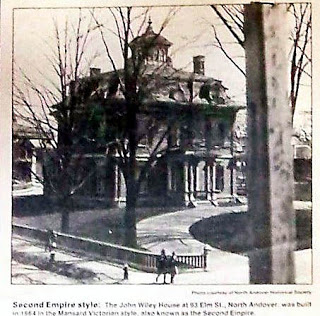

When this picture was taken in 1903, Mr. Newsholme had been water commissioner for Methuen for nine years. In 1916, the house was sold to the Gammons family who lived here until 1985. Howard Gammons, a carpenter, extended the house, while his wife kept extensive flower gardens, some of which are still there today. Soon after this picture was taken, Ashland Avenue was laid out to the left of the stone pier and the farm land became a subdivision.

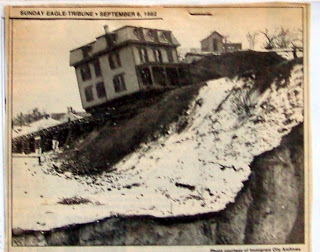

#95 - Gale Hill, Lawrence

written for Labor Day, 1992

Gale Hill home reflects care, pride taken in its construction

This is Gale Hill in Lawrence. Or rather this photograph, taken about 1890, shows a house being moved so that Gale Hill can be cut down. Margin Street ran at the bottom of Gale Hill, which was about where Gale Street is today.

As Lawrence grew, the hill - mostly sand, as can be seen in the foreground of the photograph - was removed to fill in low places around town and to become the sand in the filter beds of the Lawrence sanitary system. We think the hill was named after John Gale and his son, John P. Gale, carriage makers on Lowell Street who lived on Greenwood Street . Their company was lost in a fire in 1867, and they did not rebuild.

Look at the labor that went into moving this house. Men placed all that cribbing by hand to support that ramp which is at least 120 feet long. There were no machines to help build the ramp or move the house to its new location. All the work was done by men and animals.

The house was about 20 years old, no longer fashionable with its mansard roof. Yet it was moved. Why? Partly I think because it was built by hand, like the ramp. A saw mill had cut trees into lumber to frame the house, but each piece of lumber was cut to length on the job by a man with a hand saw.

There were no power nailers or drills or table saws, nothing run by a motor. There was no gypsum wall board. Each strip of lath had to be nailed in place to the inside walls before the plaster was smoothed on in overlapping coats. There were no asphalt shingles - that roof had slate tiles, each with two hand punched holes for the nails which held it on.

The men who moved the house understood the time and material and talent it takes to build a house. So they thought it reasonable to labor mightily to move one.

note: Readers told me I had the name wrong. As I remember today, I wrote 'Gage' when I should have written 'Gale'. I think... The name may still be wrong. The Lawrence historians will know.

#94 - 13 Milton Street, Lawrence

Gothic Revival house reflects 1850's style, taste

Come around the corner on Milton Street and for a moment you can imagine yourself in Lawrence in 1850. This house, built for a prosperous farmer, would have been surrounded by fields, orchards, and woods. Its yard would have been clean, as it is now, without foundation plantings.

Today, even though the city surrounds it, because of the lot across the way - overgrown with trees - and the park below on Bodwell Street, and especially because of how the house was sited on the brow of the hill, the house looks out over a landscape very similar to that it surveyed when it was built.

Gothic Revival, the style of this house, was the style recommended for 'rural cottages' by Andrew Jackson Downing, a popular architect and horticulturist of the time. The books he wrote circulated widely. Local carpenters copied his verandas, arched and circular windows, and steep roofs. They also copied the verge boards - the panels running up the roof's edge - and the decorative columns. But the particular patterns or scrolls and flowers on those boards were their 0wn invention.

The veranda and its brackets -the scrolls that curve along the porch roof -were meant to frame the picturesque view across Merrimack River in an arch, like a picture frame. Probably there was a similar roof with its supports and brackets at the top of the tower.

'Gothic' in the early 1800's meant 'medieval'. The first people to build in the Gothic Revival style meant to imitate the carved stone work on medieval castles and cathedrals. When the houses were built of wood instead of stone, the details changed to fit the nature of the material. 'Gingerbread' - the scroll work - became not a copy of stone tracery, but an art form in its own right.

#93 - 28 Wolcott Avenue, Andover

Bungalow-styled homes capture relaxed, vacation atmosphere

For many people, a bungalow means a cottage, the kind of place you might rent for a vacation at the lake.

A bungalow is also a style of house built from around 1900 until World War II. This one on Wolcott Avenue in Andover, shows most of the basic elements:

-Sheltering roof with wide overhangs and gentle slope,

-Brackets to support that roof and exposed rafters,

-Generous porch with sturdy columns,

-Dormers tucked into the roof.

This is a house for relaxing, casual and cozy. That inviting porch is just right for lazy days, space enough for a swing, or to set up a jig saw puzzle. It is a place to watch the neighbors and perhaps invite them up for a visit.

If you count the steps to the porch you can see how the house sits up above the street. Note the three large dormer windows and see that this house is quite big. But it appears to be both low to the ground and small. The feeling is created by the roof. It's the most important part of the house. It shelters the front porch and the house walls. Even the bay window on the first floor seems to be under its protection. The other details of the house emphasize the roof: the porch columns are big enough to support it, the exposed rafters and turned brackets draw attention to it.

Years ago, mail order companies like Lewis Manufacturing, Gordon-Van Tine, and Sears & Roebuck offered bungalows in many variations. The ladies' magazines and the builders' periodicals featured them, and many were built in the Valley - all with that roof with its overhang and its sheltering front porch.

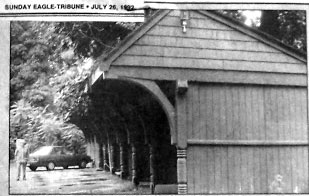

#92 Nevins Memorial Library Carriage Sheds

Nevins Library carriage sheds call to mind High Victorian era

The carriage sheds behind the Nevins Memorial Library in Methuen are unusual just because they are still there.

Once in a while behind a country church you will see some garages for the horse and buggy which brought the farmer's family to town. But in towns like Methuen, when cars became common, the land where the sheds stood was needed for other purposes.

Most carriage sheds were built around 1800 in the Georgian style. These Methuen ones are unusual because they were built in 1884, in high Victorian style. They are handsome in proportion and ornament - tall enough for a spirited horse, arched to cover a carriage. The posts are turned, the arches beveled, matching those of the library. The boards which partition the stalls have circular cut-outs and scalloped tops. Originally the end walls were covered with scalloped slate shingles, some of which remain on the north end.

When the Nevins family donated the land, hired the architect and gave the money to build the library, they also had the grounds landscaped. The trees and sculpture were carefully placed as were the carriage sheds for town residents coming to browse among the books or attend festivities in the Hall.

Broadway in those days was dirt - it wasn't paved until 1926. Most people avoided the hill altogether and used the gentler grade of Hampshire Street. They drove right past the Nevins family home, the land where Methuen's municipal offices are today. David Nevins, born in Methuen, was an importer in New York City before he returned home. His fortune came from The Methuen Cotton Co., his mill on the Spicket, which made world famous, heavy duty cotton and jute cloth.

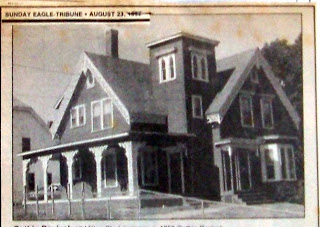

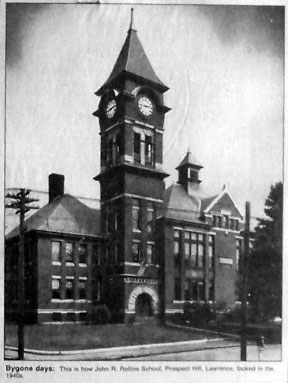

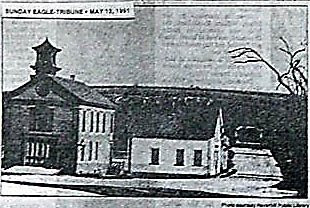

#91 John R. Rollins School, Prospect Hill, Lawrence

Architect designed school especially for young children

When the Rollins School on Prospect Hill was built in 1892, James Cunningham, a retired sea captain, owned the land. He moved a house from the site so the school could be built.

George C. Adams was the architect. I like his work, so I regularly stop to see this school of brick with granite arches and lintels and copper panels. One day I was admiring the row of circles above the arch at the main door. Each circle is really 3, one cut inside the other, like a bull's eye. I realized the shape was one easily understood by a child. Then I saw that Mr. Adams had designed the building especially for children.

The Rollins School could have been intimidating. It is big and tall. But its sections are broken into manageable sizes by the separate hip roofs and the massing of the windows. The wings are simple rectangles and the places of emphasis - the clock and the entrance - are set off by half circles, all easy shapes for children.

The school sits high above Platt Street to the left, but the main entrance is up a gentle walk from Howard Street. The granite arch over the main door is massive, strong enough to carry the weight of the tower above. But its shape is simple, a half circle, and it is low. The arch sits - visually - on the granite which bands gteh school. At the entry porch, the banding is about 2 feet high, just right for a child to touch. A child who standing there is within the arch, not dwarfed by it.

The arch was built to a child's measure. From within the space a child can look out and see across the city and beyond. What a great symbol for a school: to protect while providing the vantage point for seeing the world.

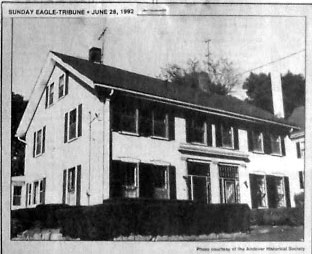

#90 Sarah H. Harding House, 6-8 Harding Street, Andover

Harding House is fine, local example of Greek Revival architecture

The style of this house, built in 1846, is Greek Revival. The flat board siding on the front is meant to look like the marble of Greek temples; the pediments over the windows like the roofs of those temples. The columns and entablature at the front doors mimic those of ancient Greece.

More than Greek Revival details dates the house to the 1840's. The technology of the time is also evident. Large windows speak of readily available, inexpensive glass. The height of the transoms over the front doors tells us the first floor has high ceilings. Houses built 100 years earlier had ceilings low enough to touch; these are at least nine feet tall. New Englanders had discovered that one way to cool a house in the summer was to have high ceilings and let the heat rise. Franklin and cast iron stoves had been invented, so rooms like these could be efficiently heated in winter.

I had always liked this house at 6-8 Harding Street. It is sited to face south, looking out across the hill toward town. Those large windows let in lots of light and give the house a sense of graciousness. I didn't expect to find it had so much history to go with it. The Harding family, for whom the street in named, owned land here and a partnership in the paper mill on the Shawsheen River. This double house was built for Sarah H. Harding in 1846, on land she bought from her mother. Sarah, a single woman, sold one side of the house to Hannah Barker, a widow. No longer was a woman alone expected to attach herself to a relative's household. She could be independent with her own property.

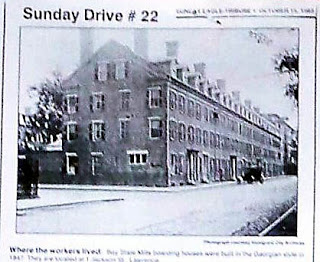

#89 Corporate Houses, Canal & Amesbury Sts. Lawrence

Architects to tour Lawrence to see buildings in classic mill city

On Tuesday, June 23, the American Institute of Architects will sponsor a tour of Lawrence and Lowell in conjunction with their annual conference which this year is held in Boston.

I asked them how they knew to come to Boston. The tour planner reminded me that Lawrence is in the history books as the classic mill city. Its plan is clear and orderly: the river the mills, the canals, the boarding houses, and then the retail thoroughfare and the common with its civic buildings. and most of it is still here to see.

The Great Stone Dam built by The Essex Company still holds back the Merrimack to divert its water into the canals. The guard locks and gate house are still in operation. The factories are here, anchored by the Ayer Mill clock tower, as is Essex Street and the North Common.

Two of the boarding houses for the millworkers remain. One is now the Heritage State Park Museum at Canal and Jackson Streets. The other is on the corner of Canal and Amesbury Streets, the right end of the 'corporation houses' in the picture above.

This is one of the first buildings in the city, designed in 1848 by Charles Storrow. Its Georgian proportions are updated with Greek Revival details - large windows and fancy brick work along the eave line.

What a wonderful sweep of buildings these were along the tree lined road, overlooking the water, a compliment to any city in the world. Today's visitors must imagine the rest of the boarding houses from the one piece remaining, but the trees, small though they are, have been replanted.

If you would like to go on the AIA tour, contact Alexandra Lee of the Boston Society of Architects.

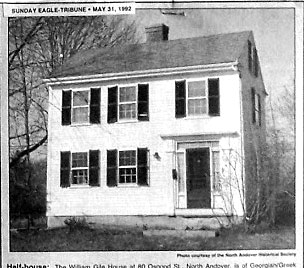

#88 William Gile House, 80 Osgood St., N. Andover

North Andover half-house meant to grow, but never did

A look at the framing of a colonial center entrance farm house often reveals that one side of the house was built before the other, that the original house looked like this house, a half-house.

A half-house was usually just the beginning. As the family grew, as fortunes improved, the matching side of the house was added. But some, like the William Giles House, above, never grew. You can see where the rest of the house would have been added, to the right, but it never was.

William Gile, a mason, had this house built about 1838, on Osgood Street in North Andover. The popular style at the time was Greek Revival, here seen in the doorway - in the design of the sidelights and in the pilasters with all their column parts: base, shaft, capital and entablature, and finally the cornice which becomes a roof over the front door. similar door ways can been seen at 179 Andover Street and 83 Academy Road. No one is certain if the carpenter of those houses, Thomas Russell, built this one too. Perhaps someone just copied.

The doorway is Greek Revival, but the house is built on Georgian lines, the accepted way to built since the early 1700's. The chimney is the only part of the traditional design which has been changed. It would ordinarily dominate the roof, rising above the ridge, serving a fireplace in each room. Here the chimney is small, a chimney for a stove, and it moved to the back of the house.

I haven't seen the framing here. Perhaps the central chimney was there originally. I suspect, however, that because William Giles was a mason he would have know about the latest heating systems. Inside his old-fashioned house he would have put the newest thing, an up-to-date cast iron stove.

#87 barn at 43 N. Broadway, Haverhill

Unknown 'old salts' carved shingles at turn of the century

How did this barn, probably built in the early 1800's, come to be covered with row upon row of elaborately cut shingles 75 years later?

Shingles had been used on walls for years, and the Centennial Celebration in 1876, reminding Americans of their colonial roots, made wood shingle siding even more popular. Victorian builders took square shingles, trimmed their edges in fancy shapes, and decorated the front gables and bay windows of mansions and cottages alike. Sometimes shingles covered a whole wall and, especially in seaside resorts, the whole house.

Perhaps, I thought, a local carpenter used this barn as his shop and displayed his skill at working in the Queen Anne style on the outside; The City of Haverhill had lots of houses waiting for embellishment! I was wrong.

A retired seaman lived here in 1900. His shipmates often stayed here when they came into port. They, the sailors, cut these shingles, invented the designs. Some of the shapes are quite simple, just a repeating triangle or square. Others - for example, those at the gable window - are ingenious combinations of circles and squares. And then there is the lace at the peak of the gable - shingles cut in scallops whose edges themselves have been scalloped.

This is folk art. Although we can imagine the men carving the detail of another shingle with a careful turn of the knife, using the skills they had perfected through long hours at sea, we don't know their names. They are anonymous. But what they created is still here for us to enjoy.

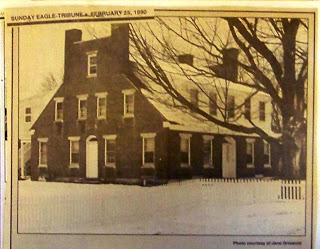

#86 - Clark-Fredrick House, 366 Hampshire Rd., Methuen

This house was built even before there was a town of Methuen

In 1700, Methuen didn't exist.

Haverhill's town line was about where Interstate 93 is today. The land in west Methuen between that border and the Dracut line was in no town, with no government and no taxes. Several wealthy Scotch families from Ipswich, taking advantage of the loophole, settled here on grants of several hundred acres.

It really was away from the known world in those days. The church in Haverhill, the center of community life, would have been at least 8 miles away over Indian trails or by boat down the river. The deed to this property, the Clark-Fredrick House, written about 1700, starts in Haverhill and lays out the route up the Merrimack River before turning inland. It refers to the property as 'bounded on the north by wilderness", what is now the Methuen-Pelham town line.

There are other references to the edge of Methuen being the frontier: Harris' Brook was once known as London Brook and Meadow, a corruption of an earlier name: Land's End Brook and Meadow. There is still a World's End Pond at the edge of Salem, NH, and Methuen. Wilderness, as the name implies, is connected to wild men and animals as well as the unknown. Choosing to live here away from society was not usual.

This house, probably not the first built on this site, is not easy to photograph with its full grown trees. As Hampshire Road curves past it, you can catch glimpses of its square shape, its massive center chimney and regular windows. That form - together with how it sits on the land - dates it to about 1720. We know it was remodeled about 1790. The return and overhang on the eaves indicate more updating was done about 1840.

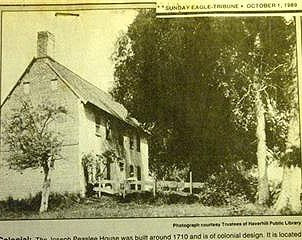

#85 - Parson Barnard House, Osgood Street, North Andover, 1715

Historic parson’s home illustrates transition from medieval design

The Rev. Thomas Barnard, pastor of the North Parish church in Andover, from 1697 to 1718, built this house in 1715. A scholar would say that Parson Barnard’s house shows the transition in colonial architecture styles from medieval to academic. What this means is that the details added to the basic structure – the hoods over the windows and the pediments over the door – were copied from older buildings, here those of the Italian Renaissance. And that the builders were influences by the theories of learned architects such as Palladio. Indeed, this house feels organized and planned as earlier homes do not. Earlier Medieval houses were utilitarian. Doors were for going in and out, windows for light and air. The inhabitants were anonymous. Here the windows and doors create the design. Their proportions and their placement in the wall give the house life. The moldings focus attention on themselves and the individual who uses them. You can easily imagine that someone inside opens the door and, stopping to feel the sunshine and enjoy the view, stands under the pediment. He is then bracketed on each side by the pilasters as if in a picture frame. The individual, of little importance in the medieval world, becomes the center of attention in the renaissance. And in this house we can see it happening.

For 200 years, people thought this to be the house of Ann Bradstreet, the poet who lived in Andover in the 1600s. Several old histories refer to this house on Osgood Street as her home, and the North Andover Historical Society, now the owner, still gets calls asking for tours of the ‘Bradstreet House”. It is open to visitors Tuesday, Thursday and Saturday, from May to September, and by appointment.

(photo from North Andover Historical Society web site)

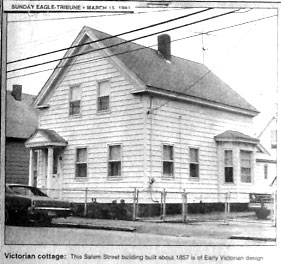

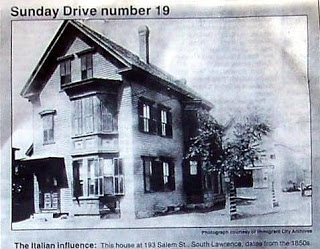

#84 274 Salem Street, Lawrence

Irish immigrants built home on Salem Street around 1857

In the 1840's, The Essex Company , the corporation that had built the Great Dam, leased its land on the south bank of the Merrimack River to its employees so they could build shanties. The family who built at 18 Dover Street ( as Salem St. was then called) were Michael and Mary Donovan and their children from Skibereen, Ireland. Their sons helped built the dam and worked in the mills. In 1856 Michael Donovan paid The Essex Co. $186. for this lot. He built this house, which was valued in the 1860 census at $800.

What he built is a house similar to those his neighbors were building up and down the street. Today standing on Salem Street, one can still pick out those early houses by their shapes - little boxes with their gables facing the street, steep roofs set on low second floor walls, the front door on one side, the windows balanced. The wide roof overhang is generous as are the frieze and corner boards. The effect is simple and pleasing. These houses lack the glamor of later Victorian buildings, but their proportions make them charming.

We know about 274 Salem Street because the Donovans' descendants still live here; and the because we can find them in The Essex Co. records and city directories now housed at the Immigrant City Archives. Seven generations of Donovans have been born here. Family members immigrating from Ireland stopped here first.

At one point a barn at the rear of the lot housed two horses. The bay window on the side with tis carved brackets was added in the 1880's, and the 1890 tornado that whipped through South Lawrence came right through the kitchen.

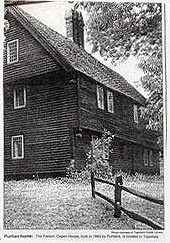

#82 - Parson Capen House, 1 Howlett St., Topsfield, MA, 1683 (03/01/92)

House Puritans built for parson was best in 1683 Topsfield

The Puritans came to New england to create a new world, a utopia based on their religious convictions. So, in 1682, when the Puritans of Topsfield asked Joseph Capen to be their new minister, the most important position in town, the house they built for him was one of the biggest and best. One indication of this was the glass in the windows - it had to be brought all the way from England by boat.

The style of the four room house was that of the medieval cottages the Topsfield citizens remembered from England, with steep roofs and massive chimneys. Those cottages provided simple shelter - the door was just an opening, as were the windows. The ornaments -wooden drops - were placed at the corners of the house, at the second floor and roof overhangs, drawing attention to the mass of the house, not the elements. The whole, whether that be the house, the family, or the community, was what mattered, not the individual.

This historic house is now open to the public in the summer. Visitors can look out across part of the 12 acres of land the Topsfield community gave their new minister. In England only the lords owned the land, but here the people could own the land they worked and be independent. For example, widows did not have to remarry, but could maintain themselves on their own land. Many of the women accused of witchcraft at the Salem witch trials in 1692 were widows living independently.

#81 Harmon House 86 Summer St

Haverhill house was stopover on Underground Railroad trail

David Harmon built this house on Summer Street in Haverhill about 1840. Its classic Greek Revival style, with the gable facing the street and the heavy banding on the corners and eaves, is intended to remind the viewer of a Greek temple.

The spacing of the columns on the surrounding porch repeats the proportions of the house. The columns themselves, tapered, round, and fluted, are a graceful counterpoint to the flat board siding on the first floor. The flat siding, meant to imitate stone, is repeated in the gable, emphasizing its triangular shape, reminiscent of a Greek pediment.

David Harmon manufactured soes, but by avocation he was a farmer. He experimented extensively with fruits and vegetables on the terraced land behind his home and built a greenhouse, visible here in the lower left of the photograph.

He was also an abolitionist. The noted men of his day, from John Greenleaf Whittier, born in Haverhill, to Fredrick Douglas and William Lloyd Garrison, visited here. His house was a stop on the Underground Railroad, transporting slaves to Canada and freedom.

Although the Underground Railroad was secret and illegal, people in Haverhill seem to have known that this was one of the stops, because there are records of this house being stoned by mobs. (later note: There are also records of fugitives openly knocking on the front door to ask for shelter and transportation north.)

Since this picture was taken, about 1870, the house has been extensively remodeled, including the addition of a tower and an elaborate back entry.

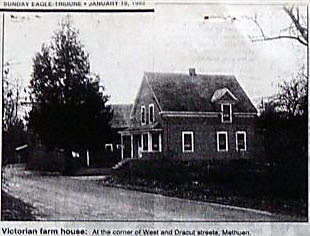

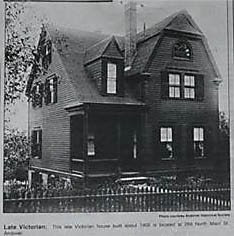

#79 - Victorian farmhouse, Dracut Rd., Methen, c1890

Victorian shows how Americans' desire for living space grew

Here is a late Victorian farmhouse in a shape that been popular since at least 1850. It is a story and a half, with a steep roof gable facing the street. Its pleasing shape (the relationship between the size of the roof and the walls), wide roof overhang and balanced 2nd floor windows on the front were all standard details for the time. The bay window and porch and the dormer window with its detailed roof date it to around 1890.

So, why am I writing today about a house built at the end of the 19th century when I said in the last article that I would focus on what it was like to live at the time of the witch trials in 1692? Because what a farmer expected to have in his home in 1890 contrasts sharply with what a farmer built 200 years earlier in the witch trial era.

The Old Red House of the last article, built in 1704, had just one room up and one down, a stair and an entry. It had a shed tacked onto the back and a lean-to set against one side. Our Colonial ancestors felt no need to distinguish kitchen space from the parlor or separate their household from its surroundings. By contrast, this house stands apart from its barns and outbuildings - the Victorian farmer who build this wanted his dwelling space separated from his working space.

In addition, although the house pictured here isn't big, it has a front room, a kitchen, a front hall, a back entry, and at least 2 bedrooms upstairs as well as one on the first floor - amazingly ample when compared to the two room Old Red House.

#78 - 'The Old Red House' 56 Central St., Andover, 1704

Home of Andover colonists reveal family had little privacy

In 1692, 43 people in Andover were accused of being witches. In Salem, "witches" were killed. 300 years later, it is hard to believe that witchcraft was such a serious crime. The local historical societies suggested I write about that time, and I liked the idea. But the landscape has become so altered over the last 3 centuries that there is almost nothing to photograph. I decided that perhaps these changes themselves might be a way to see what life had been like. So in the next several articles I'll try to touch on parts of ordinary life in 1692 in the Merrimack Valley.

"The Old Red House" was built in 1704 by John Abbott. Although it was built 12 years after the witch trials, the house shows how a family in those days expected to live. The gable on the right in the drawing is the original house: 2 stories, each floor a 20' x 20' room, with a stair entry and fireplace. As the picture shows, lean-tos and wings were added over the years. But they were not rooms for the family. With doors leading directly outside, and windows for light, not view, they were spaces for food storage, equipment and animals. The family - John Abbott, his wife and children - lived in the original 2 rooms. They had no privacy and did not expect it. This is partly because their lives were full of the labor which was necessary on a farm, but mostly because they had never known privacy. Our notions today that people need their own spaces would seem very strange to them. In 1858, the house was gutted by fire and then razed.

#77 Smiley House, 994 Main Street, Haverhill

Why do we call it a Saltbox? Because it looks like one.

The next time you are stopped in traffic on Route 125 in Haverhill, enjoy the graceful entry on this house. The pilasters on each side of the door are slightly tapered with strong bases and capitals. The door is the style of the Federal period, not the 6 panel pattern we see today. The transom is made of bull's eye glass.

The house to at least 1768. It may be older. We know that James Smiley, a soldier in the Revolution, bought it and remodeled the exterior, adding the hoods over the windows and the front entry.

We call this house a 'salt box'. The name refers to the long back roof that sweeps down from the peak almost, it seems, to the ground. When houses like this were built, from the time of the Puritans until the Revolution, they weren't called by any name. The roof arrangement was simply a way to cover a house when the first floor needed to be larger than the second. It wasn't until almost 1900 that we Americans began to notice and label our Colonial past. A salt box, then, was a box for salt which hung on the kitchen wall with a hinged top, looking rather similar to this roof.

This is, more specifically, a 'broken salt-box' because the elan to roof has been added to the main roof at a slightly different angle. It is hard to know, without taking the house apart to look, if the lean-to was an addition, ar built at the same time as the original house.

James Smiley's descendents still live here. The Smiley School, across the street, was named for his grandson who was one of Haverhill's mayors.

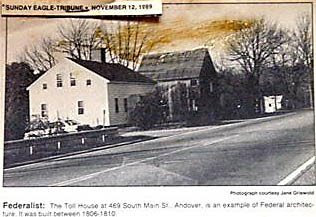

#76 Pearson Bancroft House, 9 Bancroft Rd.

Andover house fine example of 18th- century Georgian work

When this house, the Pearson Bancroft House was built in 1790, there was no road here.

The house was set on the land to take best advantage of the site. It was placed half-way up the hill, facing south for the sun's warmth. It was high enough to catch a summer breeze and be out of the damp, swampy low land. It was low enough to let the hill to the north protect it from the winter north winds. The road was just a driveway down to Hidden Road. There was no South Main Street and only fields between this house and the cape at the top of the hill.

About 1805, South Main Street - the Essex Turnpike to Boston - was built and soon after the lane was extended across to Holt Road. The jog in the map shows where the new road had to curve around the cape.

At the Pearson Bancroft House the road went through the back yard. In fact it went through the back wing of the house. So the ell was moved around to the south side and the entrance vestibule was set on the north. Now the house faced the new street.

The road was called Gardner Street until about 1909. Then the Bancroft Reservoir was built. The road was renamed for the Bancroft family who lived here for four generations, from the early 1800's to 1960.

This is just a simple farm house. It is really old. Notice the sway in the left corner and how the entrance leans against the house. It is small, only one room wide. Its windows aren't even symmetrical with two on one side of the front door, one on the other. It is plain except for the finely detailed Georgian columns and entablature at the entrance. And yet, the proportions are pleasing: each part scaled to relate to the others and create a feeling of stability and permanence.

Note: I wrote this for a class at the Bancroft School. I don't think they ever saw it or discussed it.

#75 Hartcourt - Campion Hall, Cochichewick Drive, N. Andover

North Andover's Hardtcourt once a Jesuit retreat house

Hardtcourt, or Campion Hall, the house pictured here, shows how hard it is to capture buildings with a photograph. Buildings are lived in, experienced inside and out, over days and years. A photograph shows one view from one moment in time.

This photograph shows the approach to the house across a broad field, the dignified facade with its elaborate German Baroque covered entry. The character of the mansion can only be glimpsed in the brick and limestone detailing, the dominant roof with its three foot overhang and exposed framing.

If you drive down the road to the left and then around the end of the house you will see how it sits on the brow of the hill and opens to the view over Lake Cochichewick with a conservatory on the east and a veranda all along its south side. You can see how the veranda steps down gracefully to the lawn and how the six second floor bay windows extend through the roof to become dormers with roofs flared to match the main roof. You can also enjoy how the red of the brick is repeated in the deep red paint of the wood bays and how the pale mortar matches the limestone. It is a very handsome house.

George E. Kunhardt, a Lawrence woolen mill owner, asked his friend, Stephen Codman, a Boston architect, to build this house in 1906. After Mr. Kunhardt's death the house and its land were sold to the Jesuits who used it, as Campion Hall, for a retreat center. This photograph was taken when the estate was subdivided for housing in 1974. On the estate were also barns and staff housing which are now privately owned.

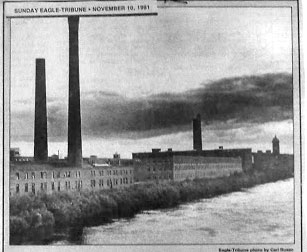

#74 Lawrence Mills, south side of Merrimack River

Lawrence mills offer unique New England architecture

When I have guests new to the Merrimack Valley, I take them on a drive past Lawrence on Interstate 495. Most of I-495 cuts through rolling New England hills, past suburban developments, with exit signs indicating a town somewhere, over there. But here, where the interstate curves down around Lawrence to cross the Merrimack River, here is a city. From the river and its mills, to the water towers on the surrounding hills, the city is laid out for every traveler to see.

And the mills! There are so many of them! So many windows and brick walls in so many long boxes set one after another along the river, seemingly held in place by those tall smokestack cylinders. Then, after all that severity, the Ayer Mill clock tower! How surprising is the elaborate shape, the arches, the clock, the double curves of the roof, the finial and weather vane - all that complexity above the simplicity of the mills.

The mills are straightforward: the necessary space for the industry generated by the water power of the river. Their simple bay pattern, a length of brick and a window repeated as many times as needed, adapted easily to changing methods of construction. The early mill walls are brick all the way through, with holes cut for windows. As glass became easier to manufacture and buildings easier to heat, the mill walls became glass, windows set within a structural frame, the brick only the skin over that frame. In the photograph that change can been seen from the older mill on the left to the newer one in the middle.

A note: If you intend to admire the view of the mills on the Merrimack from I-495, let someone else drive.

#73 7 Foster Circle, Andover, c. 1860

French designers had impact on Andover Victorian house

Back in the early 1940's, this house could have been the haunted house of Halloween stories. It was empty and in disrepair, the shutters crooked, the window panes cracked. Dust and cobwebs were everywhere and the trellis work cast eerie shadows over everything.

The house was originally the home of Moses Foster, cashier for the Andover National Bank. Probably just after the Civil War, he built it on land now bound by Elm Street, Whittier Street, and Foster Circle in Andover.

The main entrance and the tower were the latest style from France - a Mansard roof with iron cresting, substantial columns and mouldings. Aside from the tower though, this house was a conservative design, a variation on the houses New Englanders had been building for 150 years. It looks like a series of boxes set beside one another with steep roofs and balanced windows. The paired brackets under the eaves and the flat board siding on the left wing were details that had been familiar with Andover builders for at least 30 years.

Moses Foster's son, Edward, lived here until his death in 1936. Then the house stood empty for years.

When Fred Cheever laid out Foster Circle along with Johnson Acres across Elm Street in the early 1940's, he demolished most of the house. The right wing was moved to a new foundation at 7 Foster Circle. The paired brackets and the gable window with its keystone at the top of the arch - visible in the photographs - are still there. The double arched windows were saved and reused in the garage.

#72 106 Summer St., Haverhill

Haverhill's 1890 Gale House typifies High Victorian style

Haverhill residents know this house. I didn't. So they sent me off to find it. I'm glad they did.

Look at all that stuff!

Three porches, each with a different style of railing, stained glass windows on both floors, elaborate dormers, and carvings on the carvings. Pattern everywhere - much of it freely adapted from European architecture: the stained glass and carved stone work are 14th c. Gothic; the first floor window framing and the chimney corbelling are 16th c. English Tudor; the arched front entry is 12th c. French Romanesque. The arch above it on the second floor is copied from Moorish castles in 11th c. Spain. That arch is one of the nicest Moorish - sometimes called Turkish - arches in the Valley!

A.W. Vinal was the architect. He designed many row houses in the Back Bay of Boston. And this house has the feeling of a row house allowed to expand, freed from a narrow lot.

John E. Gale, the owner, was a shoe manufacturer, then director of the Haverhill National Bank, a city alderman, active in many organizations. When he died in 1916, the newspaper stated that he had lived a life "without ostentation". This house, which he built in 1890, makes that statement surprising - certainly this house asks to be looked at - until you have seen its neighborhood, The Highlands, where every corner is the site for another remarkable Victorian mansion. This was the style, expected.

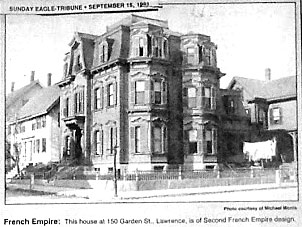

#70 150 Garden St., Lawrence

C.T. Emerson designed houses which show a distinctive touch of class

In the 1860's, C.T. Emerson called himself a carpenter in the Lawrence City Directory. By 1871, he listed his profession as 'architect' with an Essex Street address. By 1875, he had built this house on the corner of Garden and Newbury Streets as his own residence.

The corner lot allowed him space to build an imposing house with double bays. The style, Second French Empire, with its distinctive Mansard roof, was the latest import from Paris. The quoins on the corners of the main house, the heavy mouldings, all copies of stone work, make the house weighty and important - worthy of that solid granite foundation.

Mr. Emerson had a fine sense of design - see all those curves on the window hoods, and the airy touch of the roof railing where the house meets the sky. There probably was a fine view of the growing city of Lawrence from that roof. Note the elegant detail of the iron fence on the granite retaining wall and how the granite curves at the steps.

Maintaining his architectural offices on Essex Street, Mr. Emerson lived here through the 1890's.

The growth of Lawrence can be seen in this photograph: the Federal two-family house on the left was built before 1840. The Italianate house to the right was built about 1855. Both are now gone. Today when you look, you will see that Mr. Emerson's house has lost its Mansard roof and the elaborate facade is covered with white siding. Many houses in the Valley were similarly covered when Victorian architecture was no longer in fashion and its maintenance became too time consuming. Today that splendid ornamentation is often hidden from us.

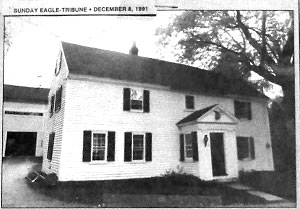

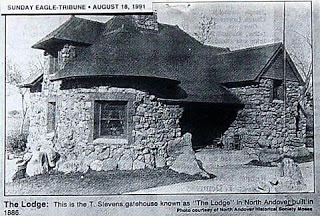

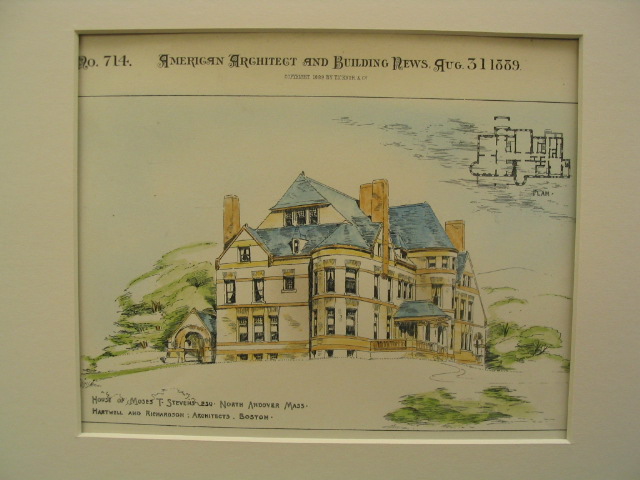

#68 - The Lodge, 723 Osgood Street, North Andover, 1886 (08/18/91)

Little house out of a fairy tale: Stevens gatehouse one of few in Valley

have always felt this North Andover house was like a fairy take, a little stone cottage hinting of inviting cozy spaces within. Is it part of the stone wall that surrounds it? Did it just grow from that man-sized boulder at the entrance? Its front porch is like a cave. The roof is whimsical with its different curves and angles, the smaller dormer protruding. The stone chimney conveys the sense that somehow the roof just slipped down over the whole mass of rock.

This is the gatehouse to the Moses T. Stevens estate, now the Boston University Conference Center (the estate has since been bought by the Town of North Andover, in 1995 - ed). It was designed by Hartwell, Richardson, Architects, of Boston, in 1886. Few such gatehouses exist in the Merrimack Valley; while we had our share of Victorian millionaires, few of them built mansions on country acreage.

A gatehouse serves two somewhat contrary purposes. First, it stops nosy or unwanted callers and tradesmen from proceeding up the road to the main house. Secondly, it announces to the public that an estate of such stature as to require protection is indeed around the bend of the lane, which the gatehouse guards. In 1886 the architect was not worried about how to make efficient use of his materials, nor was he concerned about the cost to build, or heat, or light this gate-house. He was playing with shape and form, organic form. So this little house, of rough simple stone, with a roof which goes wherever it wants, and a seeming lack of order and symmetry, appearing to grow out of the ground, is really an abstract statement about what buildings might ideally be, as other worldly as a fairy tale.

(Drawing reproduction from St. Croix Architecture website - click on image for link)

#66 22 Marblehead St., N. Andover

Ornate details make this standard house a jewel

The details on this house are fun to look at! The boards above the bay window not only end in points, but the triangles are accentuated with dots and the cutouts above the decorative ribbon.

The house itself is a standard 19th century box with its gable turned toward the street, entrance on the side, with one front room and windows balanced above - the design one expects to find on a narrow urban lot. A skilled craftsman probably lived here: Marblehead Street is a short walk from the mills along the Merrimack. But on this ordinary shape, the builder nailed a marvelous melding of details from the popular styles of the Victorian era.

Start with the frieze at the bay window. It looks like lace. Its style is Eastlake, after Charles Eastlake who wrote books extolling this kind of decoration for furniture. Americans moved his designs from the inside to the outside of their houses.

The triangles are repeated on the shingles on the edge of the second story band, but the vertical boards above come from the Stick Style, a style which showed the frame of the house on the outside. The horizontal banding that continues around the sides of the house is typical Stick Style as are the panels below the windows (not visible here).

The corner boards have a piece at the edge carved to imitate rope, a detail often labeled Italianate. The small hip roof over the gable was meant to suggest thatched roofs on English cottages or those of Swiss chalets. That emphasis at the eaves, the hip of the roof combined with the verge board curving down to rest on two sets of brackets give a sheltering feeling to the roof, the sense of a cottage, not a city dwelling.

This house was not copied from a pattern book, but designed by the people who were to live here and the builder, assembling the pieces they liked to create their own style.

This self-confidence expressed in construction is one of the pleasures of Victorian houses.

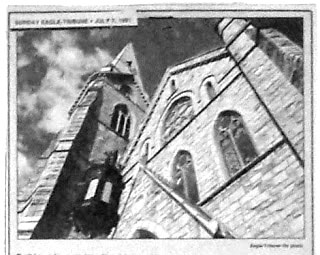

#65 St. Mary's Church, Haverhill St., Lawrence

St. Mary's recalls 12th-century Gothic cathedrals of Europe

Anyone who has built a tower with a child's blocks knows that eventually the blocks topple.

So why don't the granite block walls of St. Mary's Church in Lawrence tumble down? Because St. Mary's is built in the manner of the 12th century Gothic cathedrals in Europe, with pointed arches. Each side of these arches leans against the other side. Together they hold each other up, becoming the frame for the church. The space in the outside walls between the arches becomes windows, filled with stained glass. The space inside below the vaulting - the arches that carry the roof - becomes the sanctuary.

The point where the arch starts curving is the 'springing point', and because it carries the pressure of the stones above it, needs support. The stone buttresses - those stone ribs between the windows and at the corners that stick out - are that support. Each stone column, or buttress, pushes against an arch and keep it stable. Even the little towers on the buttresses - which you can see to the left on the front of the church - add weight to help keep the arches in place.

Look for St. Mary's as you cross the Merrimack into Lawrence. It sits in honor on the hill above the city, as do the Gothic cathedrals in Europe, like Chartres and Cologne. Built because the parish had outgrown the Church of the Immaculate Conception, it was started in 1866 and dedicated, to the boom of cannons, in June, 1871.

Its cross, now newly restored along with its steeple, rises 235 feet above the ground.

Stop and go in. You will see the stained glass windows from the inside and the magnificent space created by those granite blocks leaning against one another.

#64 - Engine House 6, Prospect Hill, Lawrence, c1895

Lawrence's Engine House 6 is practical, but also residential

In 1894, Melvin Bell, chief engineer for the city of Lawrence, was concerned that the water pressure on Prospect Hill was "too low to be of any use, only supply for an engine." So he recommended that the new fire station to be built at Howard and Platt Streets house a chemical engine, one that would contain a fire until pumpers could arrive from down the hill.

Here is that station, designed by John Ashton (who also designed the fire station in Methuen). Note how well he fit the building to its neighborhood and site - the station is strong and imposing, massive enough not to be dwarfed by the Rollins School across the street, while the tall porches, long windows and dormered roof are residential forms appropriate to the neighborhood.

The tower, nicely visible down Howard Street, was a cupola to vent the hay and oats that were stored in a loft above the horses, who lived in the rear of the station. The station entrance, set at the street corner, and the curved bay with its balcony take advantage of the view. I like to imagine a firefighter raising the flag on the balcony, then standing a moment to look out over the city.

The firehouse on Bailey Street, South Lawrence, was built from the same plans, except that the tower for drying hoses was added on the left side. Both stations boast wonderful features not visible in the photograph - stained glass windows in honor of the firefighters, carved granite lintels and plaques. The inside spaces are ornately finished with brick and wood mouldings.

#63 - Methuen Firehouse, Swan and East St, c1922

Methuen firehouse rang in a new era of civic duty

This firehouse sits quietly on the land, low-key and almost ordinary, indicating that fire protection in 1922 had become part of accepted civic responsibility - no longer something to brag about.

Yet it is a building with quiet pride. Built solidly of brick, its scale is generous: large bays for the trucks, and a triple window to let light and sun into the firemen's quarters. The large windows, and doors with glass panes, also allow passersby to admire the engines. And the broad roof with its deep overhang and turned rafters, typical 1920's residential detailing, is fitting for a station serving the newly built residential neighborhoods to the west and the truck farms on the Merrimack to the east.

But the wide lintel over the doors, coupled with brackets (much simplified since Victorian times), keep the station from looking too domestic. The lintel also supports the brick above, which is laid in a decorative - decidedly not structural - herringbone pattern. A nice touch is the row of brick headers just above the lintel that continues around the corner and down the long side wall.

The architect, John Ashton, was part of the firm Ashton, Huntress and Pratt, which had offices on Essex Street in Lawrence until the 1950's. They designed many public buildings in the area, including the B&M Railroad Station in South Lawrence and the Steven Barker School.

Another interesting fact is that when the station was built, East and Swan Streets met at an angle - the safety of the driving public did not require the right angle stop that is there today.

#60 - Rocks Village Firehouse, Main St., Haverhill, 1861

Rocks Village fire station is a landmark in Haverhill

Rocks Village built this firehouse about 1861 in order to house a hand pumper that was no longer needed in downtown Haverhill.

The village had a general store, tavern, and the ferry, and later the bridge to West Newbury. But it did not have a church or mill, so this station included its own tower and bell to summon the firefighters. That tower, with its curved roof and Italianate brackets, is just barely within the vocabulary of Greek Revival architecture, the accepted style for public buildings since the early part of the 19th century. Indeed, the whole building seems to leap from the simplicity of Greek Revival into Victorian extravagance. The front boast not only a Palladian window on the second floor, but an oriel window in the gable, while the corner pilasters are faceted (not just plain boards), the overhang is generous, and the doors are paneled in Victorian style.

Henry Ford coveted this firehouse. He wanted to move it to his museum, Greenfield Village in Dearborn, Michigan. He did buy the bridge-tender's house (to the right in this photograph, taken before 1905) and the hand pumper. But the Firemens' Association wouldn't let him have the station. Today it is maintained by the Rocks Village Memorial Society.

Note the farmland behind the firehouse in the photograph. Those are the hills of West Newbury across the Merrimack. The bridge is to the right, and today those fields are woods.

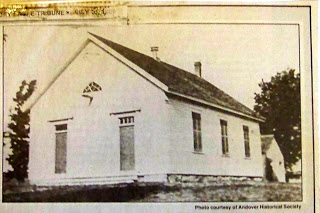

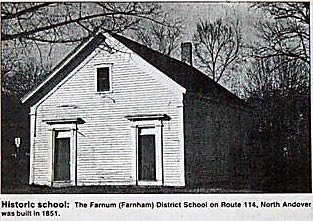

#59 - 19 Johnson St. Firehouse, N. Andover, 1851

North Andover Firehouse is Greek Revival-style design

The current exhibit at the North Andover Historical Society details the development of the Common in the Old Center by the North Andover Improvement Society. One picture shows the firehouse, which once stood across from the North Parish Church. The Improvement Society moved the firehouse to Johnson Street in order to extend the Common to Andover Street.

The Johnson Street site is now the home of the Cochichewick Lodge, A.F.& A.M. so this seemed a simple story of how an outdated firehouse became a Masonic Temple. But when I checked with Robert Hull of the Lodge and John McQuire, who knows the history of the North Andover Fire Department, the take grew more complicated.

The station had been built in 1851, when Captain Stevens donated $800 with the stipulation that the firehouse not be moved more than a 1/4 mile from the site. Built by Jacob Chickering, it was a generous size, housing the pumpers and providing meeting space on the second floor. The horses who pulled the pumpers were brought to the firehouse by neighbors when the bells rang in the church and mill towers.

The men in this photograph have names familiar in North Andover history: Dale, Spofford, Farnum, and Stevens. Warren Stevens stand to the right, with a cane and tall hat, his hand on his hip.

(important line missing here - jgr) The lot, bought for $35., was beside the Brick Store, just over a quarter of a mile away. The extra distance was overlooked, and in 1882, the firehouse was relocated. There it stood, fire station for the Old Center, for 23 more years. What happened next must be saved for the next column.

#58 - Barn/Firestation, 78 Maple Ave., Andover, c1840 (03/24/91)

History moves around while waiting for the future

Pieces of our history are not always where they began - our ancestors moved buildings all over, recycling them to new uses when the old ones were not longer relevant. So when Jim Batchelder, Andover native and member of the Preservation Committee of the Andover Historical Society, looked at the 1882 map of Andover (made from a bird's eye view) and saw the fire station on Main Street where the Barcelos building is today, he wondered what had happened to that wood frame, two-story station.

The Historical Society seemed to have no record. But when he went looking and found the fire station behind a house on Maple Avenue, the owners already knew the history of their barn. Not only had the story of the firehouse been passed down from owner to owner, but the evidence was there - horse stalls in the back, the hay door above the large front entry, a curved ceiling on the second floor creating a meeting room for the firemen. The trim on the corner boards, imitating columns, the flat fascia boards under the generous roof overhang, the gentle curve over the windows and doors were appropriate details for a public building in a thrifty New England town in the 1840's - some decoration, Greek Revival in honor of our democracy, but not too much.

Back at the Historical Society, the files revealed a copy of the newspaper, 'The Andover Advertiser', which reports that in early June, 1883, Mr. Cole moved the firehouse to Maple Avenue for use as his barn and carpentry shop. A new brick firehouse had been built for Andover Center behind the building we now call Old Town Hall.

(the Barcelos supermarket was replaced by a 24-hour CVS, sometime in the late 1990s - long the only place in town to buy very last-minute Christmas presents... -ed)

#57 Grey Court Gate House, Methuen

Gate house was summer home for Methuen hat manufacturer

Methuen's Grey Court Gate House was first a farmhouse built in 1840 by William Whittier.

In 1880, Charles Tenney, who had been born on a farm in Salem, NH, bought the house and 30 acres of land. At the time he manufactured hats in a factory on the banks of the Spicket River near the Methuen falls. When he began exporting hats to Europe, Mr. Tenney relocated the company to New York City.

While Grey Court Castle was being built, the gate house served as his summer home. His additions include the tower, terra cota chimney and Victorian window sashes. The tower was particularly stylish with its roof, a double curve called an ogee. The curve is carefully repeated at the joining of tower and house, a feat requiring great skill in order to frame graceful curves with rectangular timbers.

Soon afterward, this building became the gate house to Grey Court. In that pre-telephone era, people regularly sent notes to each other and went calling. Much as today people have unlisted telephone numbers and answering machines, people then had servants to announce that they were not at home, even if they were, or had gate houses to keep the unwelcome off their property.