Projects

Wednesday, June 25, 2008

Building to the weather - what is Original Green?

"Original Green, passive solar, building to the weather."

These are all ways to describe the same thing - how people all over the world have traditionally built to work with their specific climate.

People who look at architecture often see buildings as aesthetic symbols, or evidence of a society's aspirations. Sometimes they see buildings in terms of structure and technology. Often they focus on monuments, places intended for ceremony. Europe's Gothic cathedrals are excellent examples of all those ideas. But buildings are foremost shelter, a place to be inside - protected from the weather, whatever it may be - spaces for living. Even cathedrals had spaces where people lived - cloisters - and often served as informal gathering places.

But our ancestors spent much of their lives outside. They lived without electricity, central heat or air conditioning, so they had to understand their surroundings. They learned how to adapt their buildings to their weather, making their daily lives more comfortable by how they fashioned those buildings. And they did this with no modern technology. Instead, they understood the basic forces: sun, rain, wind - the macro-climate - and their building sites, where topography and geography create specific micro-climates. Their solutions are wonderful, inventive, brilliant. So what I'm saying, is, "Hey, pay attention! This is great stuff! It's all around us, in its marvelous variety. Maybe you are lucky enough to already live in it!"

I wrote the series which follows about building to the weather using the Park-McCullough House carriage barn as an example because it was then a museum, thus open to visitors. The series, posted in my blog, was adapted for publication in October, 2008, in the Walloomsack Review, the Journal of the Bennington Museum.

Part 1: Maximizing sun exposure

What does it mean to 'build to the weather'?

Well, look at this 1864 barn. It's the Park-McCullough House carriage house, designed by an architect for a very wealthy family. A working stable, people and horses lived in it year round. It had very little heat, a stove in the tack room, another in the living quarters. However, its use of natural forces for winter warmth and summer cooling were quite effective, and can be seen in many other barns built for ordinary farmers.

From the photograph, you can see that there is plenty of land - the barn could have been placed and set up in many different ways. Architecturally, it was placed visually to compliment the House, sitting just beyond it and framing the lawn. The main facade looked back to the House (and the flower garden and pond, which are no longer there).

The architect also considered the climate. He understood how to work with the sun. He set the long side of the barn to face due south for maximum sunshine - technically called 'solar gain'. The east end, the front, would get morning sun; the south side, sun all day; the west side, afternoon sun; and the north side, a brief bit of sun only in mid- summer. He also knew that in this part of western Vermont the wind blows mainly from the west, sometimes from the north. Wind is good for cooling in the summer, but makes things colder in the winter - technically called 'wind chill'.

How does this carriage house work with the sun to minimize wind chill?

Part 2: Creating a sun pocket

Here is the main facade of the Park-McCullough House Carriage Barn.

As I wrote in the previous post, it faces east, away from prevailing winds and into the morning sun. But you'll notice that the door - a huge door wide enough for carriages and horses - is set back. This is partly so that the hay door above is easily accessible for hay wagons - they can park underneath and unload. But the recessed space also protects against the wind and gathers the sun, making a pocket of warmth. Gardeners know that sheltered sunny nook where the first daffodils will bloom; this recessed entry creates a sheltered sunny place for horses and people.

Many buildings have a double entry that functions like an air lock: you enter through a set of doors into a little vestibule, close the doors behind you, then open another set of doors to go into the main space. It's a way to keep cold air out of a warm space (and vice versa where there is air-conditioning.)

But it's not practical to have a double entry on a barn. Imagine how big the airlock would need to be for a carriage with horses! So this recessed entry is a pretty good substitute - the doors can be opened without the wind rushing in, and on a sunny day in winter, heat may even come in.

Part 3: Original AC, or how to keep your barn from blowing up, and your horses cool

That's a pretty amazing cupola - with all its roof angles and arched vents. What a great architectural flourish at the top of the Park-McCullough carriage barn!

But it's also an important part of the cooling system. A vent at the top of a hay barn is essential, because stored hay gets hot - hot enough to burst into flame. So these vents let that heat escape out into the air. They also help to keep the barn cool for people. Heat rises, so if there is an opening at the top of a building warm air trapped inside will escape. As that warm air goes out, replacement air has to come in from someplace else. If there is an opening - a door or window - lower down in the building, new, cooler air will flow in. And if the vent at the top is smaller than the opening below, the amount of air coming in is greater than the amount that can easily go out. And more air wants to come in behind it! So the air going out has to rush, which makes a breeze.

So, in the summer, when the windows are open and the doors that lead up to the hay loft are open, a breeze will keep the carriage house, the workmen, and the horses cool..

Part 4: Eaves, at work and play

Eaves do very important work.

From a practical perspective, they help to keep the rain water that drips off of a building's roof away from its walls. This is important because rain water on the walls will become trapped water inside the walls, which quickly leads to mildew, mold, and rot. Similarly, eaves keep icicles from forming directly on a building's outer walls (which is bad because an icicle on the wall will become an icicle dripping down the wall, leading again to water inside the wall).

Eaves that stick out 6" are just barely deep enough to keep rain off, so a 9"-12" overhang is better. In this photo of the Carriage House, the eaves are 18" deep. In addition, copper gutters - now worn out and removed - sat in the curved brackets running along the edge, adding 4" more depth as well as redirecting the water. Eaves are also for play, of course - they make the carriage house fun to look at. And without eaves, this building would just be an awkward box with bumps. The length of the eaves, their edge moldings, and the rows of brackets underneath all come together to create a roof that visually shelters what's inside and delights the eye. The corbels facing both ways at the ends of the dormer windows and the at the barn's corners (see the first photo) are just frosting on the cake.

The eaves here have one other job - quite visible in the second picture. This is the south view of the west end of the barn - the eaves keep the summer sun from shining in the windows. This photograph was taken in early May, when the shadow line of the eaves is below the small windows in the stable - the sun will not shine in these windows again until late August. With the extra 4"of gutter, the windows would be shaded earlier and later in the year. Because the sun's path across the sky changes with the seasons (due to the Earth's tilt and rotation around the sun), in winter the sun will be low enough in the sky to shine below the eaves, and into those windows, bringing light and heat to the space inside. That's a lot of creative 'green' stuff for an ordinary building detail to do.

Part 5: What goes where, a no-tech solution

People in every part of the world have learned over the centuries how to work with their specific conditions - their macro- and micro- climates. This is the technical definition of 'original green'. I have used the past several posts to detail the design of the Park-McCullough carriage house, in order to illustrate how the architect worked with his knowledge of the Southern Vermont climate, while also creating a visual masterpiece.

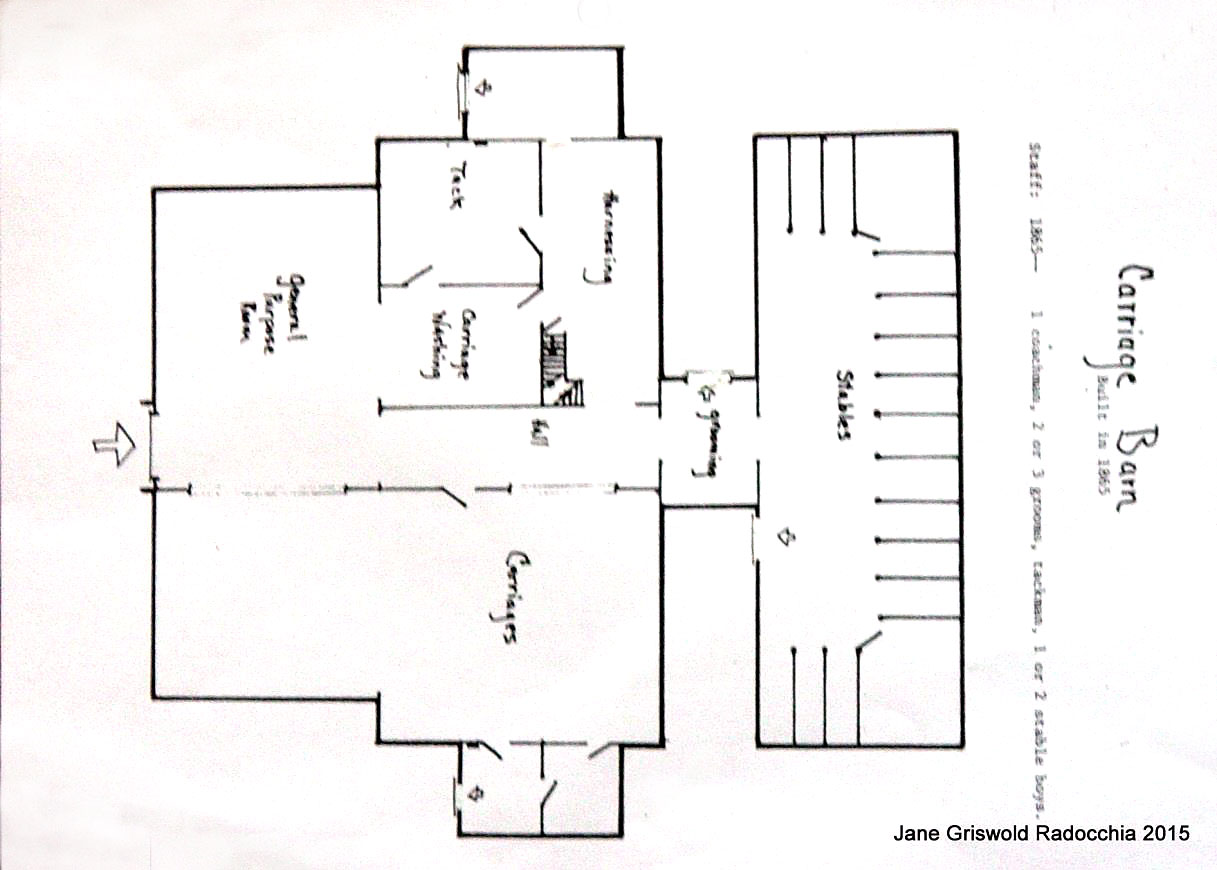

This post focuses on how the layout of the spaces inside the barn contributes to how the building works with the weather. Here's the floor plan: south is to the top, north on the bottom, the horse stalls to the west (right side), the front door to the east (left side). The general purpose room is where a horse would have been harnessed to a carriage, while the small bay to the south (top) was for carriages, maybe those needing maintenance. Note than no door opens to the north or west - only toward the mild east or the sunny south. There is a logical, efficient progression of spaces from the horse stalls to the carriages and on to the front door, with stops along the way for harnessing and tack, additions on the sides for staff quarters and repair, and space overhead for hay and grain.

This building is also designed to maximize the comfort of its occupants all year round - without technology. The long working side of the barn faces south - the previously mentioned spaces for the carriages to be readied for use, as well as the tack room holding leather bridles, saddles, horse paraphernalia. Next comes the store room for harness and the grooming room with double doors facing south, and then the stable. On the other side of the building, the north side of the main carriage space (holding carriage not in use) can be closed off in winter by 20' long sliding doors. There is a 'people' door, (only 3ft. wide,) between the hall and the north bays, bearing Trenor Park's monogram, which speaks to this north side's regular separation from the main bay.

Continuing around the building, the horse stalls on the west end need only small windows set high in the wall, literally 'horse windows', which are just the right size and height for horses to look out of. Thus, with only a few small openings, the stable also becomes a barrier to the cold west wind in winter, helped in part because the horses' own heat will keep the stable warm, making it a buffer for the main barn.

The two chimneys in the barn serve the rooms designed for people; the grooms' quarters on the north side, and the tack room, on the south. The tack room - a work room - is buffered from the elements by being set in the middle of the building, almost entirely surrounded by the carriage and store rooms. It has a large window for natural light, and the warmth of the winter sun . Even its exterior walls are set in a sun pocket, where they are protected by south and east facing walls. With a coal stove, this room would have been a cozy place to mend tack and talk about horses. The wash room is protected by its location too. It is in the center of the carriage house, beside the tack room, under the hay loft. The water used to wash the carriages drained down the sloped tin floor into the cellar. That water would not have been quite so cold here in the winter, in a room buffered on all sides. Above it all is the hay loft, filled with fabulously good insulation (hay!), which disappears in the summer when it is not needed, and reappears each fall.

And last of all, there are those large carriage house windows, which let in the welcome winter sun shine, and can be opened across from each other in good weather, to encourage summer breezes. And so we come full circle to my post about the cupola, and how it acts as original air-conditioning.

Part 6: The Big House is 'green' too

In a previous post, I described how the Park-McCullough's Carriage Barn uses 'original green' design to work with the climate. So here is a post about how the main house uses the same green techniques. The Big House, as the family called their summer home, has porches designed to shield the first floor from the strong summer sunshine. Large windows - 7 ft tall by 3 ft wide - are set across from each other, making cross ventilation easy. Then the Observatory acts as a vent at the top of the House, just the cupola does on the Barn.

The deep porch keeps the main floor in the shade, while the master bedroom on the second floor front corner gets morning sun.

Shutters from bedrooms into the upstairs hall allow air flow across sleeping rooms and up though the observatory - creating a summer breeze while preserving privacy.

The Observatory: With its vents it serves as a cupola as well as a wonderful place to look out over the countryside.

The 2 main entrances are to the south and east. The south entry is a weather entry; it has two sets of doors that act like an air lock. Both entrances are out of the wind.

The southern entrance is at the center of the photo, with the tall window allowing light into the weather entry. In the 1890's the family added a breakfast room (visible at the end of the porch). Facing southwest it is sunny all day long.

Like the tack room at the Barn, there are rooms designed to be warm and bright. On the first floor the library (later Lizzy Park McCullough's morning room) is a small room, easily heated, surrounded on three sides by the House. Similarly Laura Hall Park (Lizzy's mother) had her 'dressing room’ on the second floor, her own space where she did not need to be on duty. It's a beautiful room with a room-wide, floor-length bay window facing south, snugly set in the middle of the house, with its own fireplace. Laura did beautiful embroidery, some of which is still at the House. It is easy to imagine her sewing by the window.

The south facing bay window floods Laura Hall Park's second floor morning room with light. A morning room was a Victorian lady's personal, informal space, compared to the formal entertaining rooms on the first floor.

The layout of the House brings light and sunshine into the family space on the second floor. The main bedrooms are on the east and south sides of the House, the swing rooms to the north.

A typical bedroom fireplace with a coal insert.

The House also boasted a central heating system when it was built in 1864, but all the rooms still had their own coal fireplaces (some were later reworked to be wood burning) and all the rooms can be closed in with doors, shutters, and heavy floor length drapes. The open second floor sitting room dates from the 1890's renovation, after the central heating system was upgraded.

When I wrote about the Park-McCullough House Carriage Barn, I hoped to explain to a modern audience this basic knowledge about climate that our ancestors took for granted. I thought using a building everyone could visit (as it was open to the public) would make the ideas more accessible: you could go look for yourself. I found instead that readers thought only rich people who hired architects built to the weather.

Over time I have added posts using ordinary, vernacular buildings.

PLANTING to the weather

A post for the summer solstice

Here are 2 pictures of the same house. The first was taken this year in April, the second in June.

Note the absence of shade in April, its presence in June. The house was build around 1765 in southern Vermont. The trees were planted around the same time.

In the spring, when the warmth of the sun shining through the windows into the house is so welcome, the trees are just beginning to bud. But by June, the trees have leafed out shielding the house from the hot sun. They will protect the house though October. Then in the late fall and through winter, the sun will once again be able to warm the house.

Not only do the trees keep the sun off the house, they create a micro-climate. In their shade the air temperature will be about 10* cooler than out in the sun. This temperature change also creates a breeze, always welcome on a hot day.

In lower latitudes, the path of the sun across the sky is different. The east and west elevations are the ones which need trees for shade, while a roof overhang is enough to shade the south facade. Each climate has its own ways to shelter from the sun. For me one of the pleasures of traveling is watching how a particular part of the world builds, and plants, to its particular climate.

A Sheltering Roof, 353 Elm Street, Bennington

Written for the Bennington Banner, August, 2014.

Here I write the history of the house as well as its architecture. This picture was taken on July 5th.The date is important. Here you see how the roof extends, creating eaves that shade the windows of this house from the hot July sun. In the summer, the sun here in New England is high in the sky.

A 16" deep overhang will shade about 5' of the wall below it. Here you can see that the roof over the first floor extends the farthest, casting a longer shadow than the roof above whose shadow covers little more than half the second floor windows. The sun porch on the right side also has shallow eaves.

Later in the summer, the sun will be lower in the sky. The eaves will not cast as deep a shadow. But the tree will. Its shade will include the front of the house. In the winter months, when the sun is at a much lower angle, the eaves will not block the welcome sunshine and heat. Nor will the tree: it will have lost its leaves.

The porch may have been all screens when it was built. It was set on the northeast side of the house and held back from the front corner to allow the house to protect it from the afternoon sun. Porches like this one have often been glassed in by later owners as they are delightful places on sunny late fall and early spring mornings.

In 1925, the house lot was sold to William L Gokay for $3600.00 by Charles and Elijah Dewey, descendants of Bennington’s first minister, Jedediah Dewey. It was part of the minister’s plot when Bennington was laid out in 1761. However, in the deed the land is referred to as the ‘Swift Farm’. The Swifts were descendants of Bennington’s second minister, Job Swift.

William Gokay was a local druggist, active in the Bennington Board of Trade and the Civic League. The June 5, 1914, Bennington Evening Banner reports that he is on the committee planning the Town’s 4th of July celebration. He was 47 years old when his house was built.

The style is called Colonial Revival, mostly because the house at first glance resembles houses built when Bennington was founded: a simple white box with a center entrance and balanced windows on each side. Really the house is wonderfully eclectic: the triple and double windows were not ‘Colonial’ but modern in the ‘20’s. The deep roof overhangs reminiscent of thatch along with the small windows over the entrance are a nod toward the Cotswold cottages of rural England. The clipped roof on the gable end is referred to as a 'jerkin head' after a monk's cowl.

Since this picture was taken the balustrade on the roof over the sun porch has been rebuilt to the specification of the original blue prints. The rail adds excellent scale and finish to the house.

In 1935, Wm. Gokay died. His wife, Hazel inherited the house. She was remarried to Raymond Dunigan, manager for one of the A&Ps. Christopher and Margaret Buckley bought the house in 1941. They owned the General Stark Theater. Margaret Buckley lived here until 1987.

"beautiful variety of light and shade"

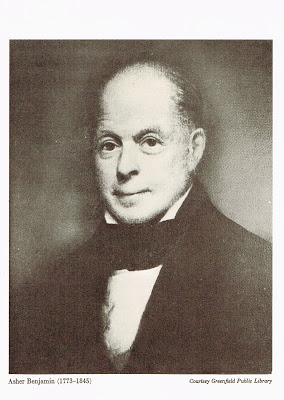

Asher Benjamin, 1773- 1843 Builder and Architect

Asher Benjamin wrote for carpenters. He starts The American Builder's Companion with ten plates of basic knowledge a 'joiner' would have needed in the early 1800's, including how to divide a circle, how to layout mouldings.

Many readers seem to skip this technical part of his books, seeing it as archaic. Sometimes historians are interested in how Georgian architecture changed from using mouldings based on the circle (Roman) to those based on the ellipse (Greek). So they note the plates and move on.

They miss the man who knows how light creates. He cares about what he is seeing so passionately that he figures out how to write about it so he can share it with his readers. I know first hand that it's not easy to put what an architect sees into words that someone else can understand!

Try this:

" In the Roman ovolo there is no turning inward, at the top: therefore, when the sun shines on its surface, it will not be so bright, on its upper edge, as the Grecian ovolo; nor will it cause so beautiful a line of distinction from the other moldings, with which it is combined, when it is in shadow, and when lighted by reflection.

...the Grecian, or quirk ovolo, ... if it is entirely in shadow, but receive a reflected light, the bending, or turning inward, at the top, will cause it to contain a greater quantity of shade in that place, but softened downward around the moulding to the under edge."

As I read his text, I met the man himself.

The quotes are from Plate IX, Names of Mouldings, American Builder's Companion, 1810.

This portrait is from the Dover Publications reprint, 1969, of The American Builder's Companion, Asher Benjamin, 6th edition, 1827. The Public Library in Greenfield was designed by Benjamin. I have seen the original portrait at Historic Deerfield, Deerfield, MA, where Benjamin built a school.

Slate Roofs 1: Looking up

Slate roofs are commonplace around Bennington, VT

- you find them on mansions, cottages and sheds.

The slate roof here is just one more flourish on an exuberant Queen Anne Victorian.

A slate roof on a garage. Many roofs are laid like this, with no pattern.

The history of slate use in Bennington

The slate quarries are just up the railroad line in Rutland County, Vt., and Washington County, NY. From the 1800's to the 1920's, slate was the roof of choice. Slate patterns vary by town. In Bennington, many roofs have the same pattern of curved and straight slate, although the number of scalloped rows may vary.

Row of houses for mill workers, with slate roofs using rows of scalloped slate

Scalloped shingles become half circles, scales, when that's all there is. This roof is on the same street as the ones shown above.

Brattleboro, Vt. roofers laid their slate in a different pattern, a double overlap:

The Creamery Covered Bridge, just off Rte 9 in West Brattleboro, has a double-overlap roof like this one.

Slate is both strong and attractive

Good slate lasts at least 150 years, poor slate only 75 years. The underlayment, flashing, and nails will wear out well before before the stone, so slate pieces were often reused. As an added decorative bonus, slate comes in various colors, and pieces split from the same block will have gradations of color. Different quarries will also have different shades and intensities of a similar color.

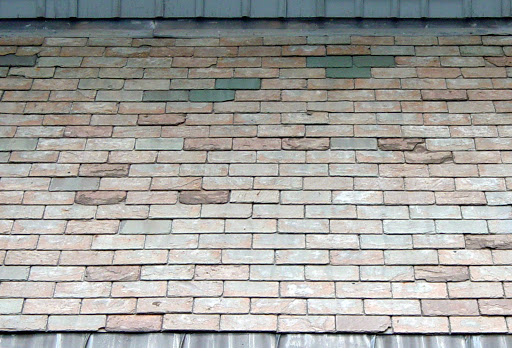

Used slate showing the range of color - even in slate from the same quarry.

The gray layer is sloughing off on the furthest left piece, revealing a reddish layer underneath.

Note double nail holes on all but one

(indicating that those pieces have been used twice)

and the vertical lines showing how the next layer of slate was laid upon these. The brown on the top half is dirt, and the little swirls are lichen.

Here are at least 4 different slate colors. The green pieces are probably patches. Some of the darkish red slate is also sloughing off and chipping with age.

Red slate has always been in short supply, and is therefore the most expensive. In 1879 three quarries produced red slate, but today there is only one.

A red slate roof on a company's headquarters.

Some owners used slate to create eye-catching roofs, and some roofers had fine imaginations.

Some quite simple houses have amazing roofs (Hoosick Falls roof, below) and some amazing mansions have simple roofs (photo at beginning of post).

Perfectly placed colors on a roof in Hoosick Falls, NY, with both scallops and hexagons.

The hexagon slate was used in Hoosick, but is rare in Bennington, just next door.

This roof uses the expensive red slate sparingly, for emphasis

The Thatcher House has slate on the walls as well as the roof, and all of it is scalloped.

Sometimes only one color is used, from one quarry. Here the church's walls and windows are what's important. The slate roof is a quiet surface, a complimentary color.

The decline of slate use

Beginning in the 1920's, if a slate roof failed it was replaced with asphalt shingles, the 'modern' solution. So the roofers who had installed slate had no reason to pass on their skills, and by the 1970's very few people could lay or repair slate roofs.

Brattleboro, may once have had a design, or the reddish slate were used for patching. Some of the slate in the lower right corner do not have enough overlap.

A roof with broken, missing (along the lower edge), and loose slate. The darker slate to the right is a patch.

Today, although we are relearning the old trade, we haven't mastered all the tricks. And sadly, many people don't value their original slate roofs.

When I went to photograph an amazing roof for this article, I discovered that it was gone, replaced since I last saw it in the fall by dull, asphalt shingles.

As this post is about the general use of slate, I have left out photos of many delightful local roofs and details. My next post will be a series of neat roofs and towers, just for fun.

In the meantime, here is a site and a book for more information:

Slate Valley Museum, in Granville, NY

The Slate Roof Bible, Joseph Jenkins, Jenkins Publishing, Grove City, PA, 2003

Slate Roofs 2: The sequel (with a focus on N. Bennington)

It is hard to decide which roofs to show, or rather, which roofs not to show, since I enjoy them all.

But they are hard to photograph. When I look at a roof with my naked eye, I can see wonderful detail or color, but that often doesn't translate to the picture - if the sun is out, the slate shines, but on a cloudy day, the colors don't show. Photos taken of north sides are best, but some roofs don't face north. Photographing from a distance generally works well, but often trees or houses block my view.

So the photos I've selected to post here may change, as I figure out how to take better pictures.

The Park-McCullough observatory, built in 1864, now missing its iron cresting. Here's a slate roof that is just roofing, while the wood arches, corbels, and brackets are the high points. The Victorian emphasis on surface decoration doesn't come to the fore for another 20 years.

The cupola of the Park-McCullough Stabling, built in 1864. Here the arched vents, the double pitch of the roof, and even the weather vane are more important than the slate.

The elegant tower of the N. Bennington train station.

Roof on a barn in Keene, NH - I imagine that when the load of slate arrived, the roofer looked over the color variation in the lot and decided he could make the diamonds.

The pattern on this roof in Pownal, VT, goes all the way around.

A hexagon slate pattern on a warehouse's Mansard roof, by the railroad in Hoosick Falls, NY

A circular tower with round columns, curly Ionic volutes on the capitals, circular slate, and a ball atop the finial - Bennington

This pattern above is on several houses and barns in N. Bennington.

The roof of the Congregational Church in N. Bennington is visible from quite a distance. People passing by on foot or on horseback had plenty of time to enjoy it, but today we whiz past in traffic. I had to take a backstreet so that I could slow down enough to really look.

Roof of Powers Market, in N. Bennington, and neighbors.

Measuring - Proportions

How did carpenters measure in 1797?

What does Asher Benjamin assume his readers know when he writes his first pattern book?

Instructions today for building a simple bookcase - for example - assumes the carpenter will use a tape measure and a steel carpenter's square.

By comparison, in 1797, a carpenter had a square and perhaps a folding rule.

He also had dividers and a compass. He used both to determine dimensions.

Here are Asher Benjamin's instructions for the moldings around a door (at the end of the descriptions for Plate 1). Click the picture to enlarge it - for easier reading!

He gives no dimensions, just ratios: 'seven or eight parts', 'one fourth or one third wide'.

The reader would have used his compass and dividers to layout the geometry, to divide a door or window width into 7 or 8 parts.

When Asher Benjamin writes his books, we were still making the parts for a house specifically for that house - no buying off the shelf.

When it came to finish work, each molding added at a door opening or chair rail was made to order, regardless of how it was measured. Uniform measurements for construction were not necessary until people wanted interchangeable parts. If your yard was 36" and mine was 35" it didn't matter.

Benjamin's introduction to geometry - his first plates - and his descriptions of how to draw the profiles of various moldings show his readers to how adapt his patterns to their specific buildings.

The Country Builder's Assistant, by Asher Benjamin, 1797, shown above, is a reprint by Applewood Books, Bedford, Massachusetts, 1992. The originals, (worn. well used and well loved!) are often available in rare book libraries.

Interlaced, Paired Ribbons: Guiloche

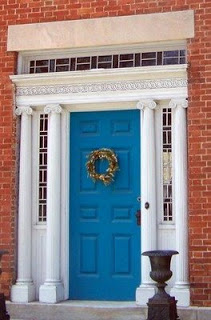

This is the door of the Hiland Knapp House in N. Bennington, VT.

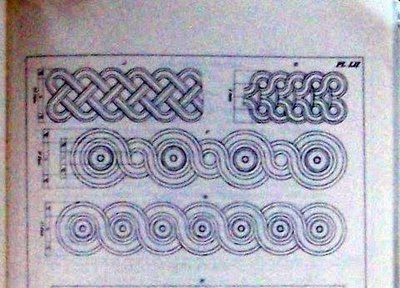

The drawing below of guiloche (paired ribbons flowing in interlaced curves around a series of voids, usually circular) is half of Plate LII from The Architect, or Practical House Carpenter, 1830, by Asher Benjamin.

This close-up - of the frieze below the transom - shows almost the same guiloche on the door as is in the middle drawing:

But the pattern on the door is not an exact copy, and for a good reason. A 'running' pattern (like the one in the drawing) does not have a beginning or an end. But a front door is the visual focus of a house; it's not on its way to someplace because it is the place.

But, adding a curvy piece above the door emphasizes the whole entrance nicely while complimenting the Ionic columns. So what's a builder to do? A simple answer might be to put one circle of the guiloche smack-dab in the center above the door. But it's still a 'running braid': visually it doesn't stand still, it 'runs'.

The builder of this house came up with an admirable solution: the pattern starts from both sides, so that the ribbons meet in the middle, in an open circle. Now your eye traces the pattern to the circle centered above the door - and stops. Voila!

(The design makes me smile.)

Geometry, Taught in 6 Plates

For years I passed over the plates at the front Asher Benjamin's books. At the time, I only wanted to see his buildings, and had no idea why he included plates on geometry and molding profiles. Now I study them.

The first 5 plates in The American Builder's Companion are instructions on basic geometry because many of his readers were "untaught." Many young men left apprenticeships to seek their fortunes, move west.They still needed to build. Benjamin provided their geometry course.

He begins:

A point is that which has position, but no magnitude nor dimension; neither length, breadth, nor thickness.

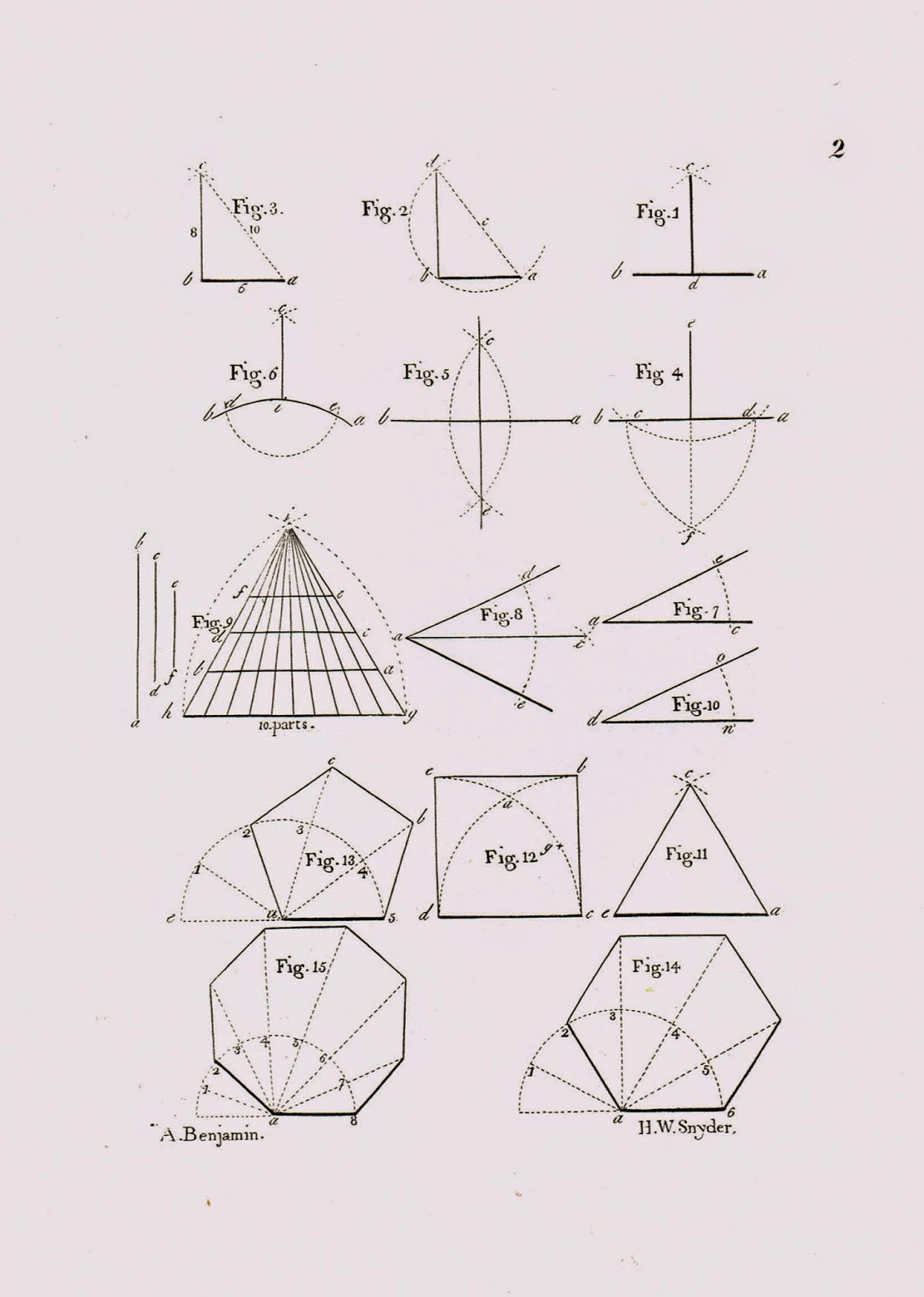

Here is Plate 2, the one we might recognize as useful in design. The Figures 3, 4, and 5 describe how to layout perpendicular lines, Figure 12 scribes a square.

By Plate 4 , Figure 3, he is describing "How to find the raking moldings for a pediment" - a semester of academic learning in 6 pages!

It's not just Asher Benjamin who cares about teaching geometry. Peter Nicholson's The Carpenter's New Guide, which ran 13 editions in Britain and the States from 1792 to 1857, spends 126 pages describing what he calls Practical Geometry. He begins with "1. A Point has position but not magnitude." (He's less flowery than Benjamin).

Neither of these pattern-book authors wanted their ideas to only be copied - they wanted their readers to possess the intellectual tools to adapt these designs to their own situations.

Plate 2 above comes from the Dover Publications 1969 reprint of The American Builder's Companion, 6th Edition, published in 1827,

Asher Benjamin

Someone I wish I’d known. His buildings do not speak to me, but his moldings, his words and pattern books do. I wrote a new post about the books in January, 2017.

See more about Asher Benjamin on my Blog.

Slate Roofs

Roofs covered by slate are all over this section of the Northeast, and largely ignored, forgotten, and unseen. These posts were an attempt to draw attention to them.

See more about Slate Roofs on my Blog.

Building to the Weather

I used the Park-McCullough Carriage Barn as an example of design knowledge we seem to have forgotten as air conditioning and heating separate us from the natural world. This series was condensed for an article in the Bennington Museum’s Walloomsack Review.

See more about Building to the Weather on my Blog.