Passing By

"Passing By" - Jane Griswold Radocchia,

Architect

A column on vernacular architecture in the Bennington, Vermont area, published monthly in The Bennington Banner, from July 2013 to the present.

The Murphy House, Murphy Road, Bennington

UPDATED February 1, 2025

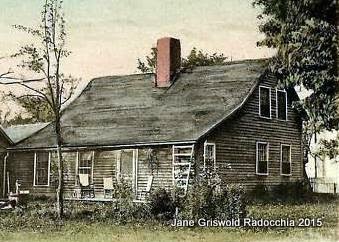

A little house, a cape, sits at the intersection of Murphy and Austin Hill Roads.

Its simple shape with few windows, a steep roof, and a center chimney are hallmarks of early Georgian houses in south west Vermont, built before the American Revolution.

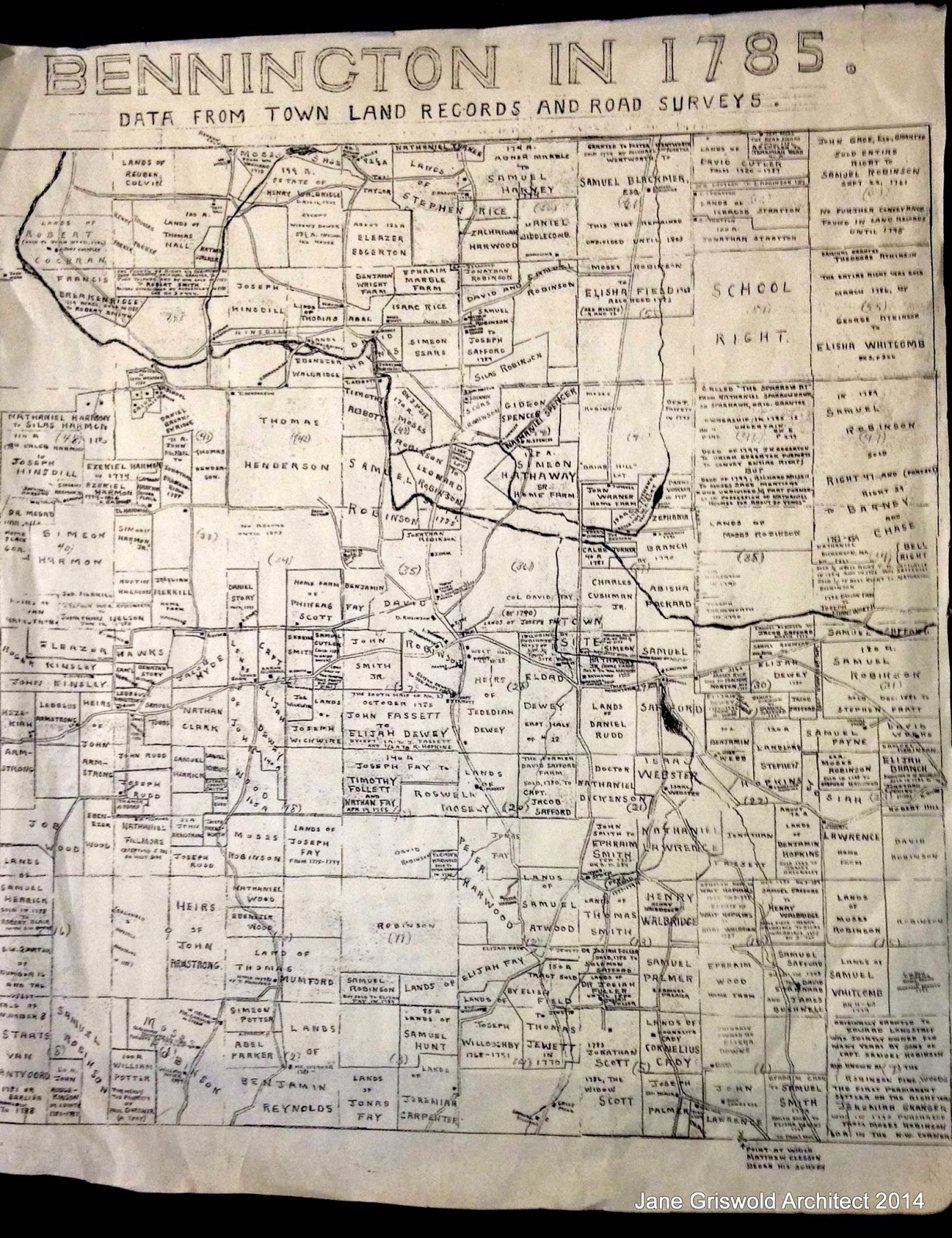

The Hinsdill Map* shows a dot here - indicating there was a house in this location in 1835. The map labels another dot, nearby to the west, as 'Breckenridge'.

The Breckenridge Papers, a family history written about 1910, are housed in the Bennington Museum. The Papers say that in 1788, John Breckenridge’s father, Daniel (1769-1847) built a “substantial and capacious house perhaps a quarter of a mile from the pioneer cabin in which he was born”. That ‘substantial and capacious house’ is the one labeled on the 1835 Hinsdill map. JY Breckenridge died in 1880. The family moved away. The house burned in 1889. A photograph of it survives and was printed in The Shires of Bennington, in 1985. The house pictured has a gambrel roof, a style which was built in Bennington after the Revolutionary War.

The ‘pioneer cabin’ is the dot on the Hinsdill map, “ a quarter mile” from the family's new house, whose dot Hinsdill labeled ‘Breckenridge’.

Bennington’s Registry if Deeds records that on April 4,1860, Micheal and Mary Murphy paid JY Breckenridge $130 for the land and house. The Murphy family owned the house and land for 148 years. They sold both in 2008.

The current owner of the Murphy House graciously showed me the fireplaces, the timber frame, the room layout, the stone foundation; all of which date the house to c. 1761, before the Breckenridge Standoff.

Daniel’s father, James Breckenridge, who came to Bennington in 1761, built the cabin. It is the dwelling which the NY Sheriff came to destroy, the house which the Bennington citizens defended.

Since the 1930's, a stone memorial has commemorated the Breckenridge Standoff in front the house built in1788. The memorial is in the wrong place.

*A copy of the 1835 Hinsdill map can be seen in the Bennington Town Clerk’s office as well as in the Regional History Room of the Bennington Museum.

The Columns of Bennington

Yes, this is a column about the columns that builders in Bennington used before 1860. There were many, most of them fluted. This is the Charles Cooper Residence.

Below it is the home, and probably the office, of Dr. Goodall.

Both have 2 story tall porticoes with dramatic Doric columns.

These houses were photographed in 1904 for the Bennington Souvenir. Both date from the 1850's and were on Main Street. The Cooper Residence was extensively updated in the 1880's as can be seen by the curved roof over the veranda that nestles between the wings of the house.

Both were, in 1904, painted several colors, no longer the classic white preferred in the 1850's.

The first house is gone, the second one also. I show them as examples of the many Bennington houses which had dramatic columns.

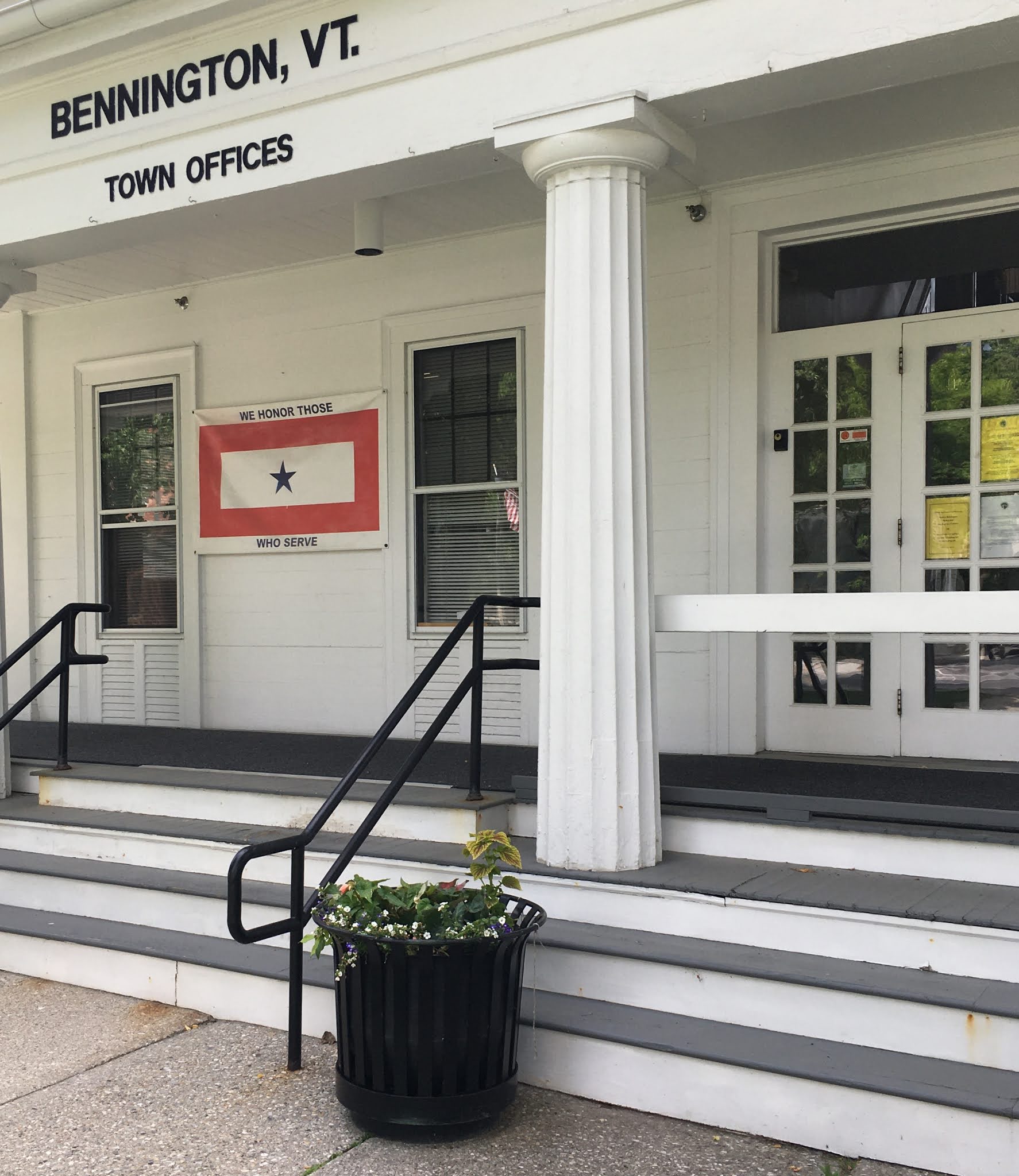

Here is Bennington's Town Offices, built in 1842 for the Root family, given to Bennington in the 1920's to be the Town's offices.

For more about the Root House, see:

https://passingbyjgr.blogspot.com/2020/11/benningtons-town-offices-originally.html

It also has Doric columns; columns with flutes, no base at the bottom and simple capitals at the top: classic American Greek Revival.

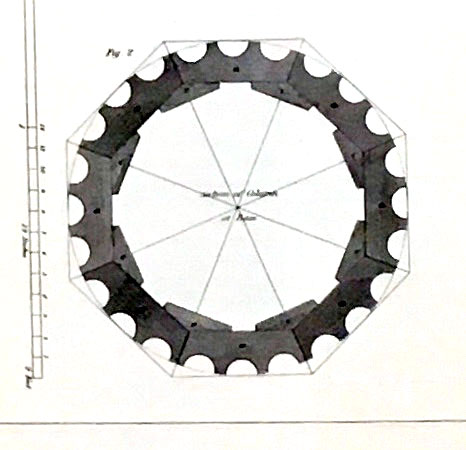

If you cut one in half it would look like this:

Long wooden shafts, 2" thick minimum, with their sides cut at angles so that when they are set side by side they join in a circle.* After three flutes are carved in each shaft, they are glued together on the edges and the inside with angled blocks and hide glue.

In 1842 this was new.

As recently as 1836, when the Norton-Fenton House on Pleasant Street was built, the columns had been made from full trees, cut, shaped, and smoothed, with added capitals and bases.

The columns in the Old First Church, built in 1805, are also trees. Local tall, straight white pines. debarked and shaped, support the balcony, the ceiling of the meeting house, and the roof as part of the attic trusses.

The next time you visit the church check the columns. You can see where tree branches were lopped off when the columns were shaped, and where the young men who sat in the balcony carved into those trees during church services.

Why did this change? Supply and technology.

The supply of tall straight trees close to the major seaport cities had dwindled. As early as 1820, the trees for the timber frames of houses along the seacoast north of Boston were being hauled by oxen and rafted down rivers from forests 50 miles away. Remember that in 1840, a 3 mile journey to town in a wagon took 45 minutes. Bringing the lumber to the cities cost money and time. Those logs was too precious to use whole.

At the same time the technology of saw mills had greatly improved. Saws could cut not just one board from a tree, but many boards at once.

Bennington still had the trees. It wanted the newest style: Greek Revival. The pattern books written by master builders and architects had plates and descriptions, including how to build the new fluted columns.

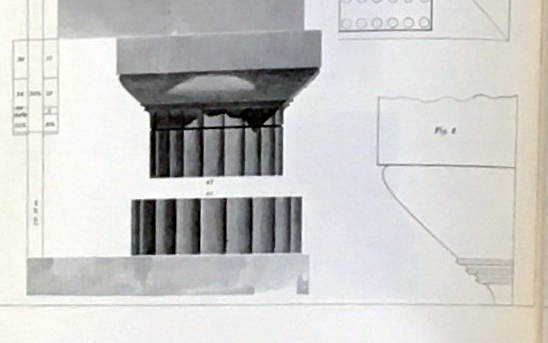

Asher Benjamin in his book, The Architect, or Practical House Carpenter, showed a Doric column with its base and capital. He included the proper proportions on the left and the profile on the right.

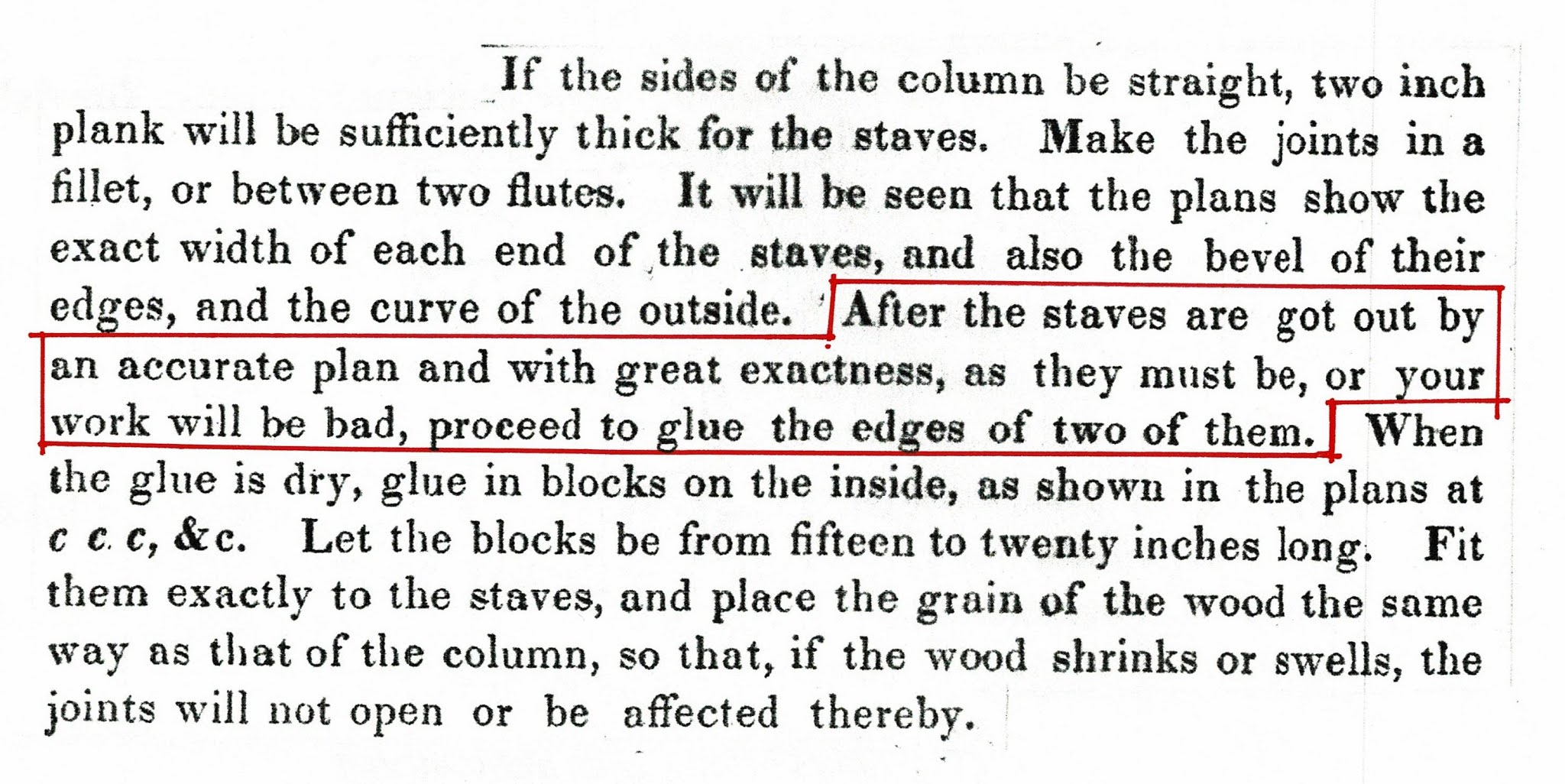

Benjamin accompanied his drawings with detailed instructions to the carpenter.* He wrote:

I especially like his explanation of the necessity of accuracy and 'exactness' in order to keep the work from being 'bad'.

Doric Columns, some much larger than those on the Town Offices, were used on Main Street, Pleasant Street and West Road, on Prospect Street in North Bennington. Those at Powers Market were brick, specially formed for that purpose.

*The image of the Doric column is part of Plate IV, titled: 'DORIC ORDER From the Temple of Theses in Athens'.

*The image of the cross section is half of Plate XXIV, titled 'Glueing up of Columns'.

*The excerpt is from Page 52: PLATE XXIV To glue up the Shaft of a Column.

All are in The Architect, or Practical House Carpenter, by Asher Benjamin. 1830; reprint by Dover Publications.

Hiram Waters, a master builder whose shop was on Monument Avenue, Bennington, owned a copy of this book. It is possible that he was the carpenter for these houses.

For more on Hiram Waters, see:

https://passingbyjgr.blogspot.com/2020/10/hiram-waters-workshop-monument-avenue.html

See also issues of the Walloomsack Review, published by the Bennington Museum.

Bennington's Town Offices, originally The Root House

When the leaves are off the trees, pause on Union Street, look toward South Street and admire the Root House. It was set there for all of us to see.

Today this is Bennington's Town Offices.

The house was built for the Root family. Elisha and Betsy Root had come to Bennington in 1833. Their son, Henry Green Root, a tin smith, had joined with Luther Graves, a peddler, to make and market tin goods. The Root family lived here until the 1920's when they gave their house to the Town.

When it was built in the 1840's it was the latest style. Facing the gable end of the house to the street was the new way; so were the wings. English gentlemen had country houses like this. So did successful merchants in the Mid-Atlantic states.

Now the style had come to Bennington. Copying the solid rectangular shape, the strong moldings, and columns of Greece temples was all the rage.

These photographs, each bringing the viewer closer to the house, help show how a visitor approaching on foot or in a carriage would have perceived the house - not as we see it today in one photograph or passing by in a vehicle.

Setting the house back from the street away from the hustle of the town, was also the latest style. It presented the house within a vista. A visitor needed to approach the house deliberately, not just by chance.

The veranda - the name used for a porch in the 1840's - helped. It was a platform: showing off the house.

It also was a place to see and be seen. It spoke of a family who had leisure time to spend on that porch.

The windows which looked onto the veranda came to the floor - you could walk through them. The house became porous, not just protection from the elements. In the winter the windows would have interior shutters and drapes. The house had the newest heating system, cast iron stoves, for warmth.

The large, fluted, and slightly tapered columns with simple capitals copied those of Greek temples.

They were not cut from one tree, but assembled from many planed and carved boards.

Columns in early Bennington buildings, for example: The Old First Church, 1805, and the Norton-Fenton House, 1836, were trees.

The gable triangle, emphasized by moldings reminded the viewers of a classic Greek pediment. The flat boards - set side by side, not lapped as clapboards are - referenced the stone walls of Greek temples.

The boards were probably made smooth by a water powered planing machine, not by hand. What a time saver that would have been!

The columns and the flat boards required newly emerging technologies that Bennington embraced.

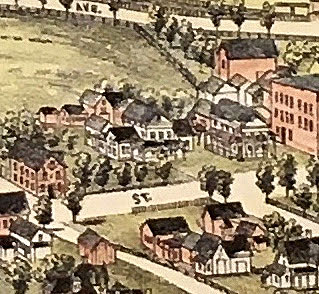

The house - seen here in the center of the colorized 1887 Bird's Eye View map of Bennington - had barns and out buildings. One - on the left at the corner of South and Elm Streets - had begun as the Root and Graves' company workshop. It is now Bennington's Welcome Center.

To the right is the house that is now used for Harvest Brewing and a restaurant and then the brick wall of Jay's Art Shop and Frame Gallery.

Here's the house as photographed by WT White or WH Sibley for the Bennington Souvenir. published in 1904.

Mary Root Mollica once told me that when she was a child (early 1930's) her Morgan horse was stabled in one of the barns.

Hiram Waters' workshop, Monument Avenue, Bennington, VT

Hiram Waters was an excellent carpenter. This is his workshop on Monument Avenue in Old Bennington, VT, built in 1835 with help from the community to replace his old shop which had burned down.

His apprentices roomed upstairs; the kitchen was in the basement. Its shape - a story and a half, gable facing the street, is standard for the time. The center door says it’s a place of business. The visitor enters into a show room. A residence would have a side entrance leading into a hall with a room on one side .

Enjoy his skill as a joiner - a finish carpenter. He understands the latest style: Greek Revival. His proportions fit his facade - not too big or too little. He includes all the right classic architectural details.

This is now residential and connected to the house to the left.

'Pattern books' were published to share the latest designs with country carpenters. We know that Waters owned at least one of Asher Benjamin's pattern books, which included detailed drawings of columns like these.

A handsome classic sequence of curves on the pedestal!

However look carefully at the half rounds that make up the column. Classic flutes curve in, here they curve out: 'reed molding'.

Did he not have the right plane? Was he inventing using the planes he had? Or did he prefer this shape?

No matter - it's handsome.

I count 6 layers of molding - 6 shadow lines for the capital from the top of the column to the frieze (the flat piece).

And then the 'rope': delicate, tucked between 2 larger simple surfaces and a plain fillet.

The running bead continues up the rake, under the overhanging eaves. It is small - best seen by a pedestrian, which is 1835 would have been almost everyone.

The cabinet shop itself is a statement of Water's ability as a builder; the rope molding is frosting on the cake.

The pattern book we think Waters owned was Asher Benjamin's Practical House Carpenter, first published in 1830. This frontispiece comes form the edition published in 1844.

Benjamin's books were very popular. He published regularly from 1797 until his death in 1845. His publishers issued later editions until 1862.

This is part of Plate XII, the architrave for an Ionic column.

Waters didn't copy the architrave or the others in Benjamin's book exactly. For example, he left out the dentils and added more moldings which emphasize the parts and create more shadows.

He also adapted the design for a free standing column to suit a corner pilaster.

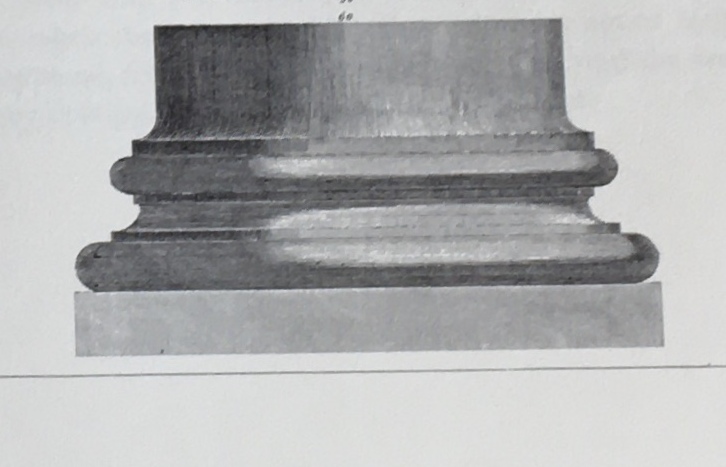

This is part of Plate V, the base for a Doric column.

The sequence of curves on Waters' base is quite similar to this.

I first posted this on Facebook. I have copied it here so it's not lost.

The images of Asher Benjamin's Plates come from The Architect, or Practical House Carpenter (1830), Dover Publications reprint, 1988.

That book does not include this frontispiece. That came from an original edition available online. I chose to use the original fonts and layout because I wanted to share with you, the reader, the cover page which Hiram Waters would have seen.

Chimneys as Decoration: The Campbell House

Introduction

What’s a chimney?

The place that takes smoke up and outside when you light a fire inside a house.

When that fire was in a fireplace the chimney needed to be right above the fire to carry away the smoke. The fireplace was inside the house; the chimney was too. Both radiated heat into the house.

The chimney was mostly invisible until it exited the house above the roof.

The chimney shown, c. 1710, has 5 flues serving 5 fireplaces.

By 1860 we had invented stoves, stove pipes and furnaces.

The pipes took the smoke to the chimney - wherever it was.

The chimney could be outside the house, visible. It became not just useful but decorative.

These stoves are from the 1895 Montgomery Ward catalog. One burns wood, the other coal. Both are definitely decorative! The furnace (right), from the Sears Roebuck 1910 catalog, is just as clearly utilitarian, belonging in the basement .

The Campbell House Chimney

William Bull, Bennington’s Victorian architect, designed this house for William Campbell at 207 W. Main Street, Bennington, in 1894. Bull knew the house would be seen from many different angles. The house sits at the intersection of two prominent streets, Main and Dewey. Campbell's factory was located across Main Street along side the river - approximately where the parking lot for St. Francis de Sales Church is today. Bull created wonderful aspects and details to be enjoyed by the Campbells, by visitors and those just passing by.

The house has several chimneys. The one most visible from Main and Dewey Street is on the right above.

It begins as stone, rough ashlar with accented corners, set against the first floor wall.

At the 2nd floor it angles and then morphs into brick, tucked behind a 2nd floor overhang.

As it rises through the eaves the brick is embellished with arches, ribs and corbels. Definitely decorative!

It is also very high –precariously so.

An iron rod fastened to the roof is required to hold the chimney securely: decidedly boring. But look: an iron confection in the center of rod’s span!

The utilitarian tie rod becomes an airy delight: just a little string up there tied in a bow.

Catalogue No. 37, Montgomery Ward & Co. Spring and Summer 1895, Dover Publications, NY, 1969, unabridged facsimile with introduction; images from Page 421.

Sears, Roebuck Home Builder's Catalog, The Complete illustrated 1910 Edition, Dover Publications, Inc. NY, 1990; image from page 98.

Brick in the Valley

The Barnett House, c.1840, sits looking over the river valley on Caretaker’s Road, in Walloomsac, NY.

Graceful, upright, red brick, white entrance with sidelights, marble lintels and water table: Neo-Classical.

It is one of many brick houses built here beginning in the 1820’s. The Academy in Old Bennington, 1821, was probably the first, followed by others on Monument Avenue, in North Bennington, and Shaftsbury. By the 1840’s handsome brick houses graced at least 9 farms in Hoosick and Walloomsac.

The quarries on Mt. Anthony and West Mountain could have supplied the marble. Where did the brick come from?

After the Civil War there were brick yards on Rollin Road in Shaftsbury, on Clay Hill in Hoosick Falls, and Coleville Road in Bennington. Before 1860? I can find no record. During research at the Hoosick Township Historical Society, Charles Filkins, Phil Leonard and I considered transportation. Brick was manufactured in the Hudson Valley. How might it have come here in such quantity?

Turnpikes were straight roads laid out beginning in the1820’s to ship goods to market expeditiously. Ones that still bear the name are the Mud Turnpike in Boyntonville, the Tamhannock Turnpike in Pittstown, Turnpike Road in Cambridge. In Bennington, West Road in Bennington,VT which stopped at Pleasant Valley Road was extended to Mapletown in Hoosick, NY.

A farmer taking his produce to Troy for the market would have returned with an empty wagon. Even a small load of brick would have made the trip more profitable. Many trips would have meant many bricks. Plausible, but are we right? Maybe.

The name ‘turnpike’ comes from the pole - a ‘pike’ - that barred a private road. When the toll was paid the pike was turned; the traveler could proceed.

6/7/2015 What is a 'water table'?

It is the board or stone at the bottom of the wall just above the foundation. Often foundations were irregular, being built out of stone. The water table stuck out, insuring that water running down the face of the house was jettisoned away from the foundation. At the Barnett House the foundation - above the ground - is made from beautiful cut stone, laid up with care. It is not irregular. Still the mortar would have been lime and sand, not cement - protection was still useful.

This house, c. 1825, has a brick foundation and a stone water table. Here the window sills are stone, but the lintels over the windows are arched brick, not stone as in the Barnett House. I think the technology for cutting the wide marble lintels did not yet exist.

On the brick facade 'ghost lines' can be seen above the entrance where a porch was once added and then removed.

The Luther Graves House

June 4, 2015

125 Washington Ave., Bennington, VT

Photograph courtesy of the Bennington Historical Society Published April 25, 2015

Behind the Elks Club on Washington Avenue is a white brick building with red trim and a Mansard roof. In 1867 it was the carriage house for Luther and Sarah Graves’ mansion which sat where the Elks Club is today.

Luther Graves, a salesman, and Henry Root, a tin-maker, joined forces in 1831 to manufacture and peddle tin ware: buttons, spoons, cups, plates, pans, stove pipes. A few years later they set up a factory in Bennington. The town had no tin-maker; there would be no competition. As the company grew Graves could no longer peddle; he ran the office. By 1860 the company had 100 peddlers working out of 4 branch offices. Graves and Root were wealthy men. Graves then turned, in 1863, to establishing The First National Bank of Bennington. Root became the bank’s vice-president.

In 1867 Luther and Sarah Graves built this 3 story brick mansion, a statement to their success. At first glance at the photograph it seems much like the Park-McCullough House built 3 years earlier. Both have belvederes, sloping Mansard roofs, arched windows, wrap around porches with slender Italianate columns. However, this house feels more solid. It is built of massive brick not lighter wood. The window hoods and arched pediments at the roof line are weighty. The 2 story double chimneys stand like soldiers. The house was sited so that those passing by looked up at the house and knew its strength: a good house for a banker.

The Graves family built 2 bank buildings on Main Street and 4 houses in Bennington, all architecturally interesting. This house was torn down in the 1960's.

Joe Hall tells more of the history of the house on WBTN’s Bygone Bennington No. 46. It can be found on-line.

Here is the drawing of the Park-McCullough House by the architects

and a photograph for comparison. The drawing is in the collection of the Park-McCullough House. I think the photograph is too. but I have no attribution.

The Defoe-Mooar-Wright House

March 10, 2015

The Defoe-Mooar-Wright House,

Main St. Pownal, VT

Postcard published by BW Hale,

Williamsville, MA,

1909

This postcard, from 1909, shows the back of the Defoe-Mooar- Wright House in Pownal, c. 1750, probably the oldest house in Vermont. A book could be written about the house. I cropped the view because I am only writing about the roof!

It shelters the original small 4 room house: 2 rooms with fireplaces downstairs, 2 upstairs under the eaves. The roof was ordinary, a gable. The 4 windows on the right side belong to the original house. When a storage wing was added on the back the roof was extended to cover it. The slope of the new roof didn’t match the first one; it wasn’t quite as steep.

Soon the storage space became living space. It was a common way to grow a house just as today we enclose porches and sunrooms, expand into garages.

People considered such roofs normal. If they noticed that dramatic slope sweeping down from the high peak close enough to the ground to be touched, they didn’t mention it. They called the additions ‘lean-tos’.

Fast forward to 1876: The United States celebrated its Centennial; we were 100 years old! America had a past. Old houses, so different from those the Victorians were building, were part of it. We began to distinguish one old house style from another, to name them. This roof reminded New England historians of the ‘salt boxes’ with sloping lids which held salt in their kitchens. Historians in the South saw these roofs as ‘cat slides’.

At the last Bennington Historical Society lecture someone asked when do we begin to notice that a building isn’t just old, but worth looking at, worth preserving?

I think we see older houses anew when they are 80 to 100 years old – when they were built by people we didn’t know. They aren’t just old, not just nostalgic. We don’t quite know what they are about. We have to consider why they look like that. We give them names so we talk about them with others.

The Defoe-Mooar-Wright House uses Dutch framing around an English layout. It has brick nogging. It faces the river, not the road. One of its fireplaces is in the basement. Its ownership history is not fully understood. Naming its roof a salt box is only the beginning.

The 1789 Map of Vermont

Feb 2, 2015

Driving west on Northside Drive I look across the land where La Flamme’s furniture store once stood, over Furnace Brook to the stone house and its wood frame neighbor at the junction of Northside Drive, Harwood Hill and Harmon Road. I am seeing a village, The Flats.

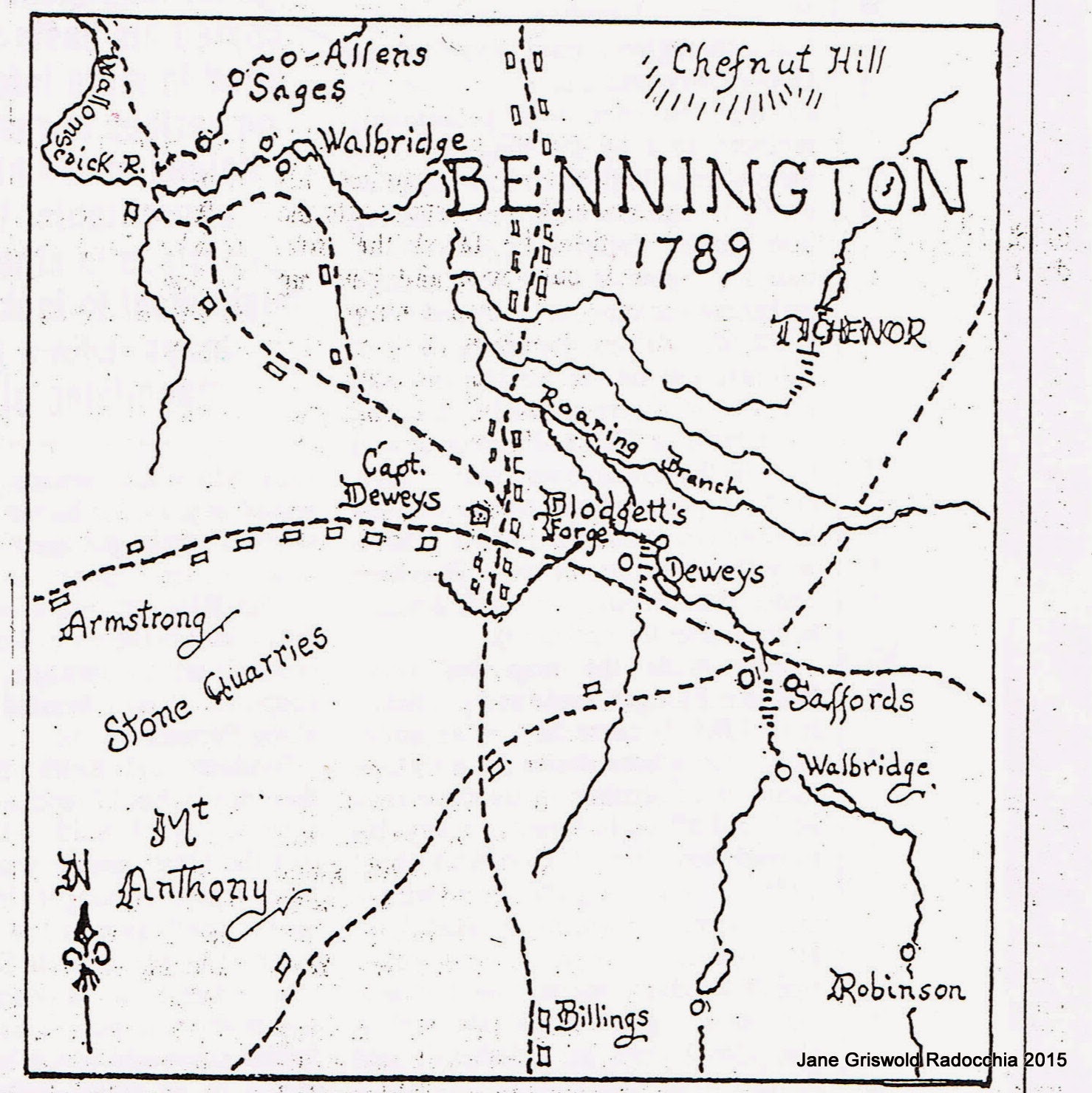

Based on the age of the houses I thought The Flats was settled about 1830. I was wrong; the community is on the 1789 Map of Vermont, a map I barely knew.

Tyler Resch, the Bennington Museum’s Librarian reminded me of this map after my December column on Benning Wentworth’s grid. Joseph Parks, Bennington historian and Banner columnist, wrote about the Map of Vermont in 1998. He described the map as about 2 by 3 feet with Bennington “compressed onto a space barely an inch square”. At the time Joe Parks asked Marie Sheldon Hine to redraw that square. I reproduce her rendition here.

The map maker, William Blodgett, owned a blast furnace in the center of town, just about where North Street crosses the Walloomsac River. The forge is clearly labeled on his map. Blodgett hoped to make more maps and gain work as a land agent. In the inch allotted to Bennington he drew 4 roads. One, mostly gone, ran from Carpenter Hill beside Jewett’s Brook across to Safford’s mill at Beech and Main Streets and up the east side of the valley. The other 3 roads we know today: Rte. 9; the way to North Bennington through the Henry Bridge (Fairview, Vail, Austin Hill, Murphy, Harrington Roads and Water Street); and Monument Ave.

Of course the Monument didn't exist in 1789. Monument Ave was the main road in town. It continued north from Old Bennington, down the hill, across the river and up Harwood Hill toward Shaftsbury. Blodgett’s map shows 10 grist and saw mills, and about 40 houses; 10 were in Old Bennington. 10 more were at The Flats and at the beginning of Harwood Hill.

A village at this junction makes sense. Although Blodgett left out Northside Drive, at least a path was here, coming from East Road, running along the river, crossing Furnace Brook, leading on to Walbridge’s mills at the Paper Mill dam and then to North Bennington. At The Flats it met the main road between Bennington and Shaftsbury. Here also was the fertile river bottom farm land between the Walloomsac, the Roaring Branch and Furnace Brook. Both houses at the intersection face down the road, welcoming the traveler. They are not haphazard. Designed with classic proportions, they were built for successful farmers. The Flats was a place, a ‘somewhere’, not just a stoplight on my way to the store.

Tyler Resch shared authorship of the article with Joe Parks. Victor Rolando researched the location of the forge. The column details Blodgett’s life, his iron forge, his time in Bennington. A good read it is available at the Bennington Museum library.

Town Maps

December 29, 2014

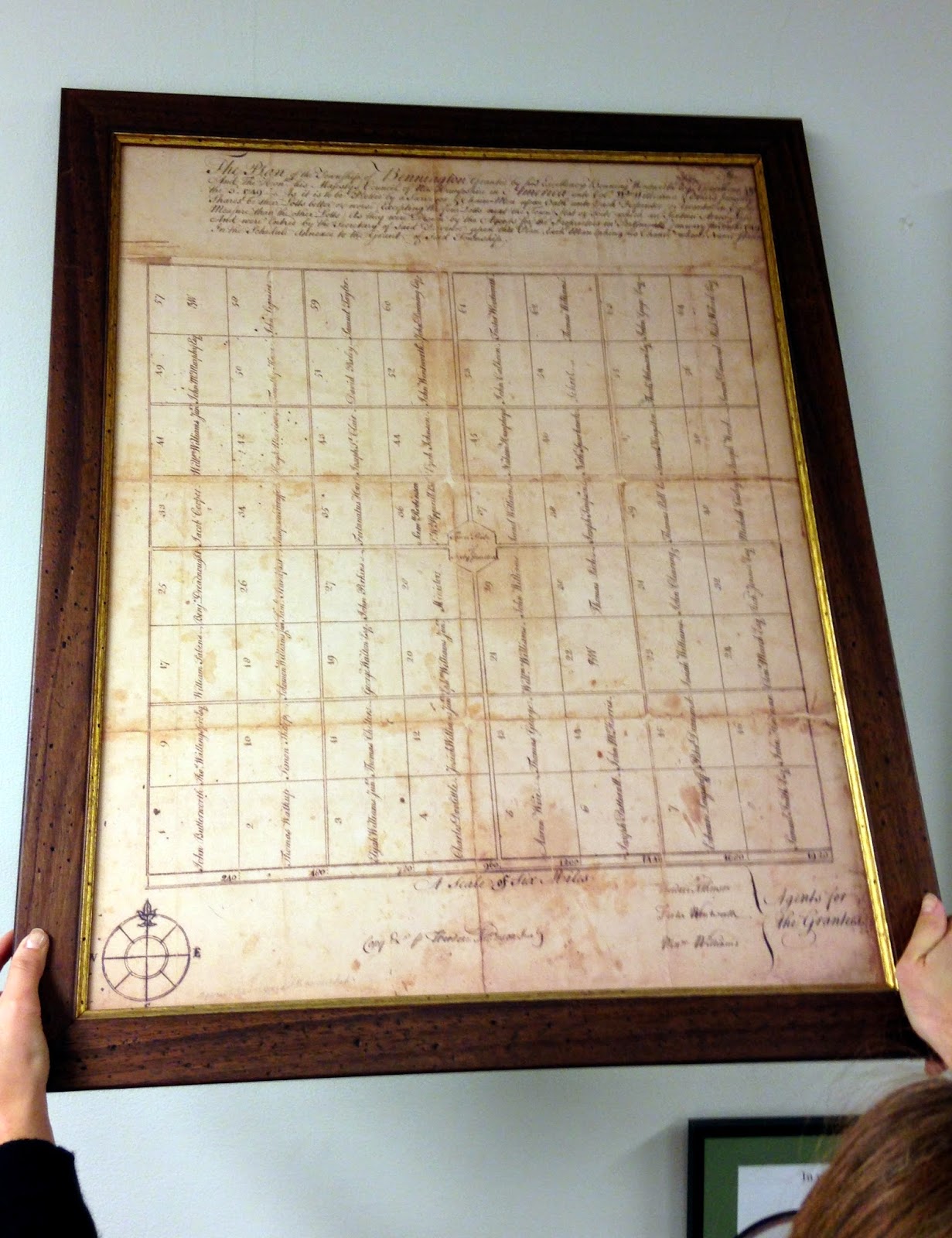

Written in honor of Tim Corcoran, Bennington’s Town Clerk who died in November

Town Hall walls are filled with maps from different eras showing many aspects of the Bennington. The maps in the Town Clerk’s office are not fixed. Tim moved them around. He knew them. He shared them. A copy of the 1835 Hinsdill map sat in front of the fireplace by Tim’s desk for a long time. Then it migrated over to the door. I asked Tim which was the oldest. He said the map on the wall in the lobby. The photograph is this map. The hands holding it are those of Cassandra Barbeau, Tim’s Assistant Clerk, now our Town Clerk. It is not what I hoped Tim would show me. I wanted a map, c. 1770, that showed early settlement patterns. I wanted early roads, bridges, dams, paths across the mountains, the way to the next town. Instead the oldest map is just rectangles, a grid. It has no interest in the actual place. Benning Wentworth, Royal Governor of New Hampshire, made the map in 1749, naming us after himself: Bennington. He was never here. He had those boxes neatly drawn so he could sell the acreage they represented to his cronies. His cronies bought deeds to land they never saw and sold the deeds to their cronies. Everyone made money. No one came. Eventually people who did want to live here bought the deeds. They arrived in 1761.

The grid ignores our topography. The Walloomsac and its tributaries cut diagonally across the Town. We have hills, valleys, water courses, the Green Mountains, Mt Anthony and Whipstock Hill.

I assumed the grid was so awkward that it disappeared. Even though Tim said it was our oldest map, I considered it irrelevant. However I kept driving down very straight roads. Were they the remnants of grid lines?

On the back of the Hinsdill map in the Town Clerk’s Office I found glued a study map; Bennington in 1785. Drawn by unidentified researchers about 1975, it lays out the lots and owners of record in 1785. Showing how the land was divided 25 years after the first settlers arrived, it confirms that paths did develop on some of the imaginary lines laid out by Benning Wentworth.

Starting on the east side of town, here are the roads that began as boundaries between parcels:

-Chapel Road, Coleville Road but not East or South Stream Roads;

-Fuller Road, both ends;

-N. Branch Street and Country Road, bordering the Branch family land;

-Rice and Mattison Roads;

-some sections of Monument Avenue, North and South Streets, and Harwood Hill;

-Murphy Road, including the sharp turn on the east end which follows the Hinsdill and Walbridge boundary;

-Austin Hill Road;

-West Street and Knapp Road in N. Bennington: boundary for the Colvins and Halls;

-the western ends of Vail and Walloomsac Roads, Houran Road.

A copy of the 'Bennington in 1785' map is also available for study at the Bennington Museum library.

Note:

I date the study map from the hand written notes - ie before wide spread use of computers and copiers. By the mid 1980's labels could have been typed and pasted to the map.

However, perhaps the research was done for Bennington's 200th anniversary, 1961. or its 225th, 1986.

I hope this column will bring forth someone who knows so I can give proper credit and thanks to those who produced the study map.

AND it has: The Bennington Museum has the Blodgett map of 1787 which I will see next Monday... more news later!

The Huntington House at Peters Four Corners

November 18, 2014

I like to come through Peters Four Corners in Shaftsbury to see again the land and the houses. I come especially to see this, the Huntington House, upright, positive; that porch ready for a visit. The house doesn’t sit quietly like its neighbor across Tinkham Road but commands my attention.

The Corners is named for the Peters brothers, the roads for the Coulters, Myers and Tinkhams who had farms here.

Before those families the Huntingtons were here.

Amos Huntington came with his family to Shaftsbury in 1779. During the Revolution he was imprisoned in New York City by the British after being captured at the Battle of Hubbardton. He probably built the cape which used to sit in a fold of the land on Coulter Road.

The Huntington family genealogy says Amos ”devoted himself to the peaceful pursuits of husbandry,” that he was “emphatically a peacemaker”. His great-grandson, Myron Huntington, 1827-1880, is noted as having “owned and improved the old homestead”, this house that had been his grandfather’s.

Myron married Mary Cross in 1850. They expanded the house with this tall 2 story front wing and a broad porch that suited the technology that was changing how people lived. Cast iron stoves could heat high ceilinged rooms much more easily than fireplaces. Coal heated more evenly than wood. Kerosene replaced candles. New devices were making household chores and farming easier, leaving time for that front porch. The railroads moved everything and people too. This house speaks to that upbeat spirit. It happily meshes both Greek Revival and Italianate styles. Its wide corner boards begin and end with moldings imitating Greek columns. The gable is finished as a Greek pediment. The Italianate double porch posts are tall and thin, delicate compared to the solid house behind them, but it all works.

Soon after the Civil War, Myron and Mary Huntington moved to Illinois with their 6 children. Other Huntingtons still lived in the area, but this house changed owners.

Peters Four Corners is named for Maurice Coulter Peters, 1905-1990, who lived here. His brother, Donny, lived in the cape on Coulter Road. Neither updated their properties. Donny’s house was beyond saving when he died.

Maurice’s house lacked basic amenities. In 1990 it had a cistern and a light bulb. The next 2 owners have repaired and restored what the Huntingtons built, improving plumbing, heating, and electrical systems. They continue to work on siding, flashing, and roofing. Meadow Valley Farm has brought the farm buildings back to life.

I, one who simply passes by, thank them all for their serious work and labors of love.

11/19/14: I have now learned that the house was owned by the Peters family before Maurice was born. I have heard many stories some of which I include here.

I was told that Maurice's mother (the first wife) was a proper, hard working, farm wife who fed the men their dinner at noon and then changed into her afternoon attire so she could properly entertain her friends in her living room and on the front porch.

Donny's mother, the second wife, - as reported by those who saw her - was a beautifully dressed woman: furs, soft leather gloves, cashmere.

Maurice was married for about a year. The house west of this one was built for him and the new wife.

In his later years he would sometimes move down into the basement during winter cold spells. I am told that he lived simply and felt no need to modernize.

I have also been told that the Colonial across the road was built by the Huntingtons. As I did not do a deed research for these houses I do not know. I relied on genealogy and maps.

107 Branch Street, Bennington, VT

October 7, 2014

30 years ago 107 Branch Street was considered just a house, nothing special. Today we call it a ‘Four Square’ and I’m writing about it. What happened?

It got old! This style of house was very popular from about 1900 until the 1930’s. Over the years these houses became ordinary. Then as they aged they gained a past; we looked at them with nostalgia. We saw that they reflected an earlier way of life; we gave them a name. Now they are ‘vintage’ and will soon be ‘antique’!

The name originally came from the floor plan, a square divided in 4 parts: 4 rooms on the first floor, 4 on the second. Today it more often refers to the shape.

Four Square houses have a pyramid roof over a 2 story box and usually a generous front porch. They were built in many variations in Bennington and all over the United States. The shape was efficient, simple to build, and could easily accommodate regional preferences. For example, a porch could have turned railings on the New England seacoast, square brick posts and balusters in the Midwest, or a solid half wall with Doric columns as was built here. The style was so popular that Sears Roebuck - and the other mail order companies which shipped kit houses by rail - copied the style. The mail order houses were never trendsetters; they copied successful designs.

The definition of ‘Four square’ is ‘forthright, solid, strong, honest’. Visually I think this house lives up to its name.

In the early 1900’s people passed this house every day as they walked to work, to shop, to catch the trolley on Main Street. The house, set off by the small front yard, was part of the streetscape, part of the neighborhood. The front porch encouraged that feeling. It was, and is, a place to see and be seen. Earlier houses often faced the sun, and looked out over the land. Grand houses were placed to impress the approaching visitor. Workers’ housing clustered in the shadow of the mill. This house, and the many others built in this era, was set to interact with the community.

The shape of the house is simple. It has none of the bays or turrets so popular in the Victorian era. It is a box sitting solidly on the land. The siding adds to the sense of stability: the clapboard on the first floor is sheltered by the shingles on the second. The deep eaves are protective, and the roof – a pyramid – is a strong, stable shape.

The few frills add to the feeling. Those corbels under the roof emphasize the broad eaves. The attic dormer is within the roof. The porch columns’ style is Doric, symbolic of strength and stability.

The Banner photograph is in black and white. The house itself has great color: creamy siding and trim, dark blue shingles. The original paint colors would have been similar – light color on the bottom, darker muddy brown, green, or rust for the shingles, perhaps a third color for trim.

The Colvin family originally farmed this land. Their farm house is now 901 East Main Street. The Rockwoods, Colvin cousins, owned land on both sides of Branch Street and ran Rockwood Hosiery Mill on Main Street. In October, 1922, Arthur Rockwood sold parcels on the east side of Branch Street to Lee Warner. I think Warner was a builder because 6 months later, in April, 1923, he sold this house to William and Mattie Heiderstadt. 6 months: that’s just about enough time to build a straightforward house.

Note: Many of the people who lived in this house left no public history. William Heiderstadt grew up on a farm in Nebraska. He was about 40 when he bought this house. He and his wife lived in Bennington for 15 years before moving to New York to run a dairy farm. He died in 1947.

The Stone School House, Hoosick, NY

September 16, 2014

September 16, 2014

The Stone School House on the corner of NY Rte 22 and 7 at Stewarts' in Hoosick is a landmark: we all recognize. It was a real school from 1842 until 1917. While the name refers to its grey stone walls, the roof is what I notice: how the ends curve out over the walls at the eaves.

Eaves are useful. They make shade in summer. They deflect the wind in winter. They shed snow and water away from the walls and foundation, helping to keep the structure dry. Most eaves are simply extensions of the roof. They don’t usually swoop out. This is a simple one room school house with only a cast iron stove for heat. Why the fancy eaves?

.

The school was built in a time when there were no electric fixtures to switch on for light on winter afternoons or cloudy days. Sunlight was essential so the windows on both sides were big. Set high on the walls they let light flood over the students onto their work. Because they were near the top of the walls the lintel above the windows did not need to hold up many rows of stone. This is good: stone is heavy. To see the problem look at the wood lintel over the school house door that faces Stewarts: it has bent under the weight of the stone above it.

The windows were in the right location, but eaves at the ordinary angle would have shaded the windows and blocked the light. The curve set the eaves above the windows, letting in the light, while allowing the eaves to work, sending rain, snow, and ice away, providing shade and wind protection, and - an extra bonus! - giving the school a welcoming air.

The school was built in 1842 by John Grant, an Irish stone mason, hired by Sarah Bleeker Tibbits. She wanted a school for the children of her tenant farmers. The Tibbets lived in Troy. Their summer place, their ‘country seat’, included what is today the Hoosac School and the Tibbits State Park. Sarah’s husband, George M. Tibbits, helped establish the Walter A. Wood Mowing and Reaping Co. in Hoosick Falls.

The quilt poster hung between the windows is a Hoosick wide project. Colorful oversized quilt blocks are all over town, well placed to surprise and delight.

Two notes on previous columns:

First: Jim Dunigan corrected the history of the property transfers at 353 Elm Street, Bennington. His mother, Hazel Dunigan, was the wife of William Gokey, who built the house, not his daughter as I had written. Mr. Gokey died within the first year of their marriage. Hazel inherited the house and later married Raymond Dunigan. Her son remembers playing in the house as a small child. He told me his mother was a dietitian at the hospital and ran a tea room called the White Elephant in the old stone blacksmith shop on South St. which is now the Welcome Center.

Second: More about the supervisor housing on Rte 346 in North Pownal: Charles Kokoras was the builder. He emigrated from Greece as a child with his family. As the oldest son he went to work at 16 in Peabody, MA. When Michael Flynn bought the N. Pownal mill, he sent Charles to the factory to turn it into a tannery. Kokoras became the maintenance supervisor at the tannery. He used the tannery maintenance crew to build the supervisors’ houses. Later on he built the first North Pownal fire house and over the years served as fire chief, constable, tax collector, and selectman for Pownal.

My informant, who wished not to be named, told me Charles Kokoras liked revising the plans of the houses as he built them. His daughter lived in the one on the east end.

The italicized notes are additions to the original column. I also rewrote some sentence structure.

A Sheltering Roof, 353 Elm Street, Bennington

August 4, 2014

This picture was taken on July 5th. The date is important.

Here you see how the roof extends, creating eaves that shade the windows of this house from the hot July sun. In the summer, the sun here in New England is high in the sky.

A 16" deep overhang will shade about 5' of the wall below it. Here you can see that the roof over the first floor extends the farthest, casting a longer shadow than the roof above whose shadow covers little more than half the second floor windows. The sun porch on the right side also has shallow eaves.

Later in the summer, the sun will be lower in the sky. The eaves will not cast as deep a shadow. But the tree will. Its shade will include the front of the house. In the winter months, when the sun is at a much lower angle, the eaves will not block the welcome sunshine and heat. Nor will the tree: it will have lost its leaves.

The porch may have been all screens when it was built. It was set on the northeast side of the house and held back from the front corner to allow the house to protect it from the afternoon sun. Porches like this one have often been glassed in by later owners as they are delightful places on sunny late fall and early spring mornings.

In 1925, the house lot was sold to William L Gokay for $3600.00 by Charles and Elijah Dewey, descendants of Bennington’s first minister, Jedediah Dewey. It was part of the minister’s plot when Bennington was laid out in 1761. However, in the deed the land is referred to as the ‘Swift Farm’. The Swifts were descendants of Bennington’s second minister, Job Swift.

William Gokay was a local druggist, active in the Bennington Board of Trade and the Civic League. The June 5, 1914, Bennington Evening Banner reports that he is on the committee planning the Town’s 4th of July celebration. He was 47 years old when his house was built.

The style is called Colonial Revival, mostly because the house at first glance resembles houses built when Bennington was founded: a simple white box with a center entrance and balanced windows on each side. Really the house is wonderfully eclectic: the triple and double windows were not ‘Colonial’ but modern in the ‘20’s. The deep roof overhangs reminiscent of thatch along with the small windows over the entrance are a nod toward the Cotswold cottages of rural England. The clipped roof on the gable end is referred to as a 'jerkin head' after a monk's cowl.

Jim Dunigan, son of Hazel and Raymond Dunigan, called me the morning this was published in the Banner to tell me that Hazel was his mother, and had been the wife of Wm, Gokay, not his daughter. He also wanted to know if the house was well taken care of, remembering living there as a small child.

Cupolas and Belvederes, Park-McCullough House and Carriage Barn, N. Bennington

July 2, 2014

We in farming country know that cupolas on barns are for cooling. Hay can get hot, hot enough to make a fire. But we know the physics: hot air rises. A cupola has vents that let that heat escape, cooling the hay and protecting the barn.

The Justin Smith Morril House, home of one of Vermont's US Senators, in Stratford Village, VT, is an historic site, open to the public in season.

The famous screens of Baltimore were painted for privacy.

Sieves and food covers had long been made of woven wire with a fine enough weave for flies but not mosquitoes.

I do enjoy Mr Wickwire's name and his wire weaving patent - seems just right: did he dream of wire and wicks as a child?

The belvedere is not a 'widows walk' which is a platform at the top of a house for looking out to sea, to the horizon, to watch a ship departing or coming back to port.

In the Adirondacks and along the Mohawk River/Erie Canal such observatories are sometimes known as 'widows walks', probably because many of the settlers in that part of NY migrated from the seacoast.